Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

1959 – The Year Abstract Expressionism Took the Spotlight

There are years that change everything quietly. No riots, no manifestos, no wild headlines. Just a steady shift in the atmosphere, a movement that begins behind the gallery walls, in the quiet of high-ceilinged studios and echoing museum halls. For Abstract Expressionism, that year was 1959.

Long before terms like “blue chip art” and “investment-grade painting” became standard vocabulary in the art world, there was a time when artists painted not to sell, but to survive — to make sense of a world in turmoil, to grapple with meaning. Abstract Expressionism was born in that crucible. But by the end of the 1950s, something had begun to change. Money entered the frame. Institutions followed. Fame, both seductive and complicated, knocked on the studio door. And artists — Rothko, de Kooning, Newman, Gottlieb — stepped into a new kind of spotlight.

This article is an exploration of 1959, a year that didn’t make a loud noise in the headlines but echoed deeply in the modern art world. It was the moment Abstract Expressionism began to mature — not just as an artistic movement, but as a cultural force with market weight, institutional approval, and international presence.

Rothko’s Red and Brown – Color Fields Meet Capital

In 1959, Mark Rothko was no longer just a spiritual painter grappling with silence and awe on canvas. He was a market presence. That year, he earned over $61,000 (after gallery commissions) from the sale of seventeen paintings — an enormous sum for any artist at the time. Among those sales were significant works like Four Darks on Red (1958), purchased by collector Ben Heller for $8,000, and Red, Brown and Black (1958), acquired by none other than The Museum of Modern Art.

To contextualize: the average annual salary in the U.S. in 1959 was under $5,000. Rothko was making twelve times that by painting quiet, glowing blocks of color.

This wasn’t simply about economics. It marked a turning point in the cultural valuation of Abstract Expressionism. Rothko’s color field paintings — once seen as esoteric, even alienating — were now understood to possess emotional power and visual magnetism worthy of institutional preservation and private investment.

And yet, despite his success, Rothko was deeply ambivalent about commodification. He resisted selling to buyers who didn’t “get it,” worried about the spiritual dilution of his work. 1959, therefore, wasn’t just a year of triumph — it was the beginning of a new, more conflicted era for artists who saw painting as a moral and metaphysical act.

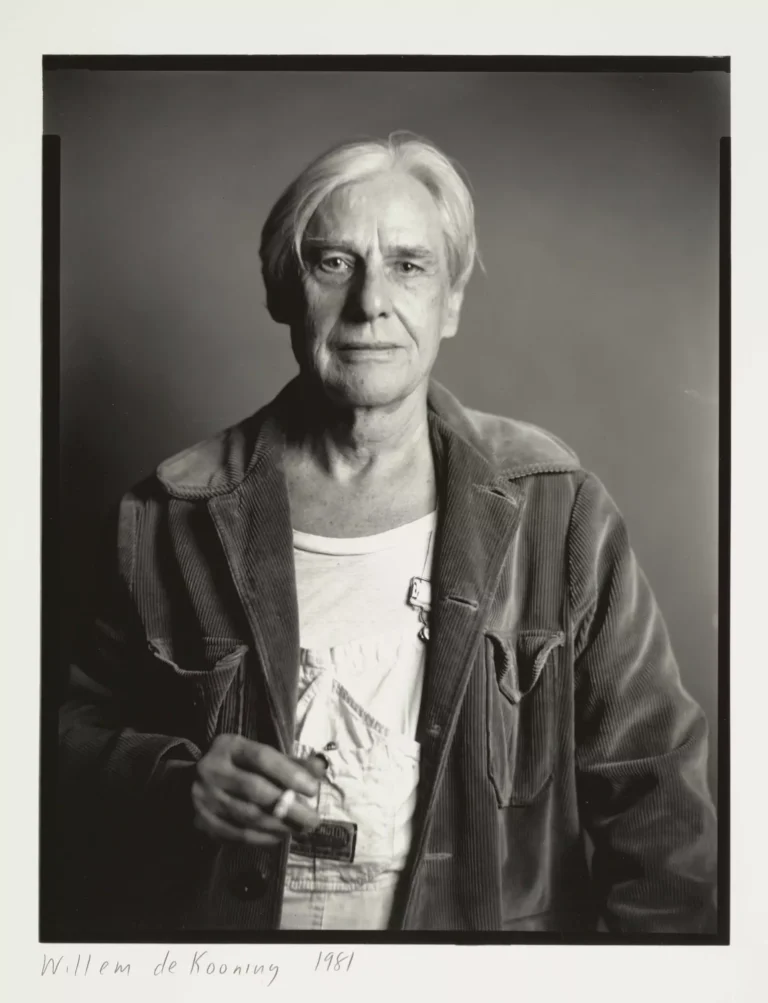

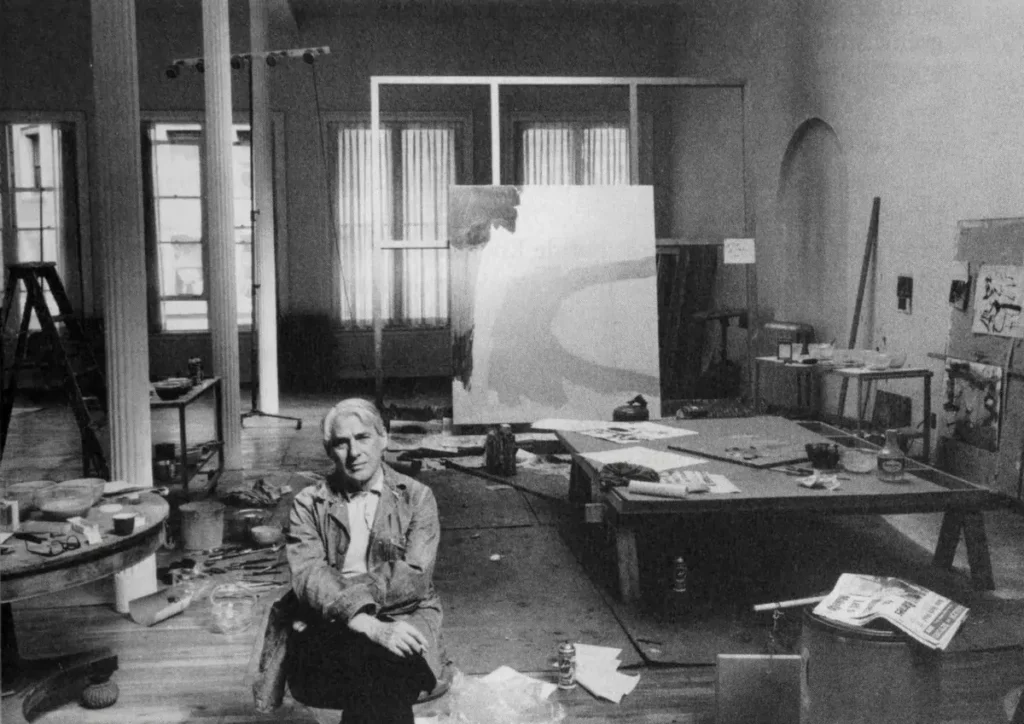

Willem de Kooning Moves Up (Literally)

Another seismic shift — quieter but just as symbolic — came when Willem de Kooning moved his studio from a rougher, more makeshift setting into a loft at 831 Broadway. The new space had a skylight, wide windows, and the kind of real estate footprint that signaled, however subtly, that Abstract Expressionism had arrived.

De Kooning had long been the most visceral and physical of the Abstract Expressionists. His brushwork was volcanic; his canvases looked like they’d survived a storm. And yet, here he was, moving into an airy, well-lit studio in Manhattan’s more elegant core.

In an art world where place is often synonymous with power, this wasn’t just a studio upgrade. It was a metaphor for the movement’s ascension — from scrappy outsider status to institutional recognition.

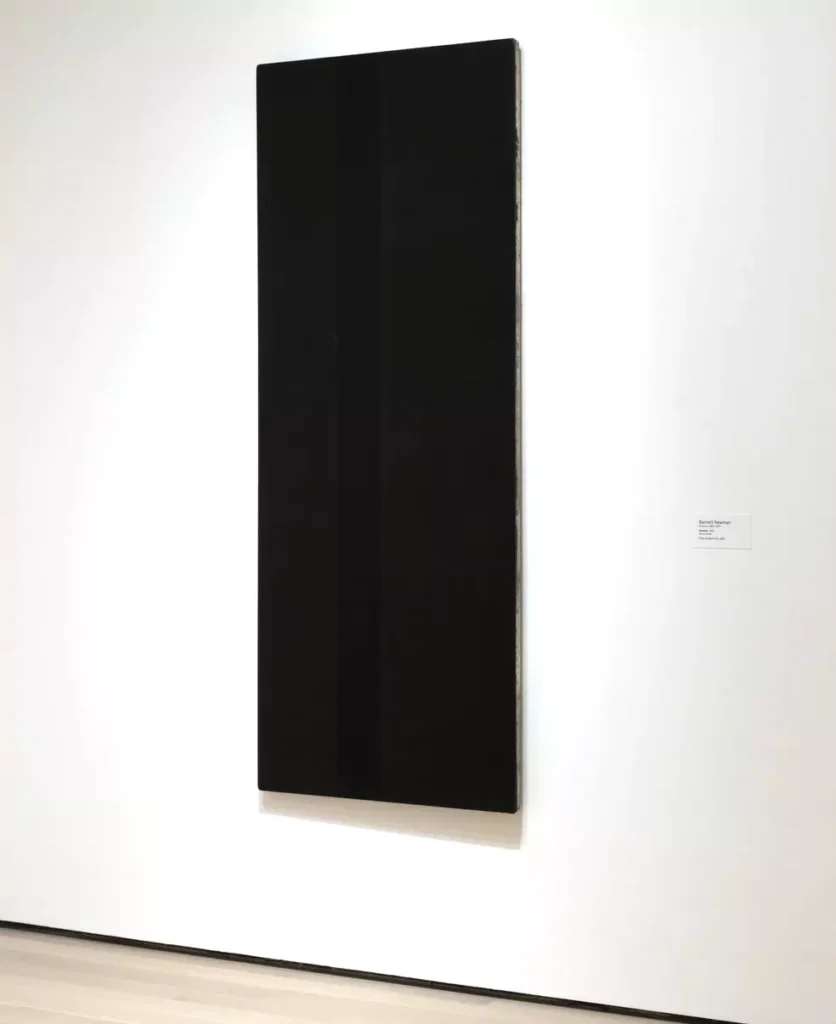

Barnett Newman and the Museum Seal of Approval

For years, Barnett Newman had been the dark horse of the movement — an artist whose minimalist vertical “zips” baffled many. But in 1959, the Museum of Modern Art acquired his painting Abraham (1949), making it the first Newman work to enter a public American collection. In parallel, Day Before One found its way into the Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel.

These weren’t just acquisitions. They were anointment rituals. Once MoMA gave its blessing, the art world listened. Newman’s work, once dismissed as too austere or too abstract even by Abstract Expressionist standards, was now seen as essential. His retrospective later that year at French and Company — organized by Clement Greenberg, no less — sealed the deal.

Twenty-nine paintings from 1946 to 1952 were displayed, many for the first time. Critics and collectors began to reconsider Newman’s role, not as an outlier, but as a quiet pioneer.

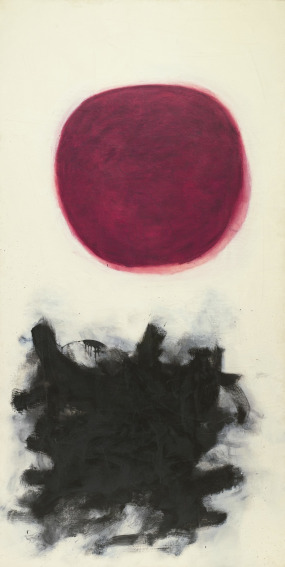

Adolph Gottlieb’s Dual Debut – New York and Paris

Meanwhile, Adolph Gottlieb made transatlantic waves with exhibitions at André Emmerich Gallery in New York and Galerie Rive Droite in Paris. Clement Greenberg, the art critic whose words could make or break reputations, wrote the catalogue text — a gesture that lent further gravity to Gottlieb’s evolving status.

Gottlieb had long straddled the line between abstraction and symbol. His “burst” paintings, with their planetary orbs and floating glyphs, felt like cosmic meditations. In 1959, with major shows in two cultural capitals, he wasn’t just showing work. He was offering a visual language that spoke across continents.

This international reach is significant. It showed that Abstract Expressionism, often viewed as a uniquely American phenomenon, was now speaking globally — not through politics, but through pure form and feeling.

The Name Game – Rothko’s Legal Declaration

On May 16, 1959, Mark Rothko legally changed his name from Marcus Rothkowitz to Mark Rothko. To some, this might seem like a footnote. But in the context of 1950s America, it was a powerful statement.

The change was, in part, about assimilation. Anti-Semitism was still very much alive in American life and institutions. A name like Rothkowitz carried with it all the markings of outsider status — foreignness, ethnicity, history. “Rothko” was cleaner, more neutral, more ‘modern art.’

But this was also about branding. The name “Mark Rothko” had begun to appear in reviews, museum labels, and sale receipts. It was becoming not just a name, but a signature, a label, a presence.

In that sense, Rothko’s name change was a final brushstroke — one that completed his transformation from immigrant intellectual to American modernist icon.

Kingmaker in the Background – Clement Greenberg

No portrait of 1959 is complete without mentioning Clement Greenberg. Though not an artist himself, Greenberg’s critical writings were instrumental in shaping Abstract Expressionism’s ascent. His support for de Kooning, Rothko, and Newman wasn’t passive. He curated shows, wrote catalogues, and constructed an intellectual scaffolding that lifted these artists from the margins to the center.

Greenberg understood the stakes. He wasn’t just advocating for a style — he was defending an ideology. In a Cold War America eager to differentiate itself from Soviet Realism, Abstract Expressionism became the perfect ambassador: free, expressive, non-didactic.

1959 was a year in which Greenberg’s influence peaked, not because he said something new, but because institutions and markets began to reflect his earlier convictions.

Art Meets Money – A Complicated Romance

The convergence of money, museums, and modernism in 1959 didn’t destroy Abstract Expressionism — but it certainly changed its trajectory. What began as a kind of aesthetic rebellion had become a form of cultural currency. Painters who once worked in relative obscurity were now navigating contracts, commissions, and critics.

For some artists, this brought validation. For others, it brought tension. The purity of vision that defined early Abstract Expressionism was now being tested against the realities of fame and finance.

But perhaps this tension is part of what gives the work its lasting power. Those color fields, those ragged lines, those monumental canvases — they aren’t just expressive. They are records of a moment when American art grew up.

1959 – A Threshold Year

Looking back, 1959 doesn’t scream revolution. There were no manifestos issued, no dramatic stylistic breaks. But the quietness is deceptive. Beneath the surface, Abstract Expressionism was crossing a line — from private to public, from marginal to mainstream.

The artists were changing, the world around them was changing, and the very idea of what it meant to be a modern painter was shifting. Rothko was earning, Newman was being acquired, de Kooning was moving up, and Gottlieb was going global.

It wasn’t the end of the movement, but it was the end of the beginning.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!