Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

Artist: Dora Carrington (1893-1932)

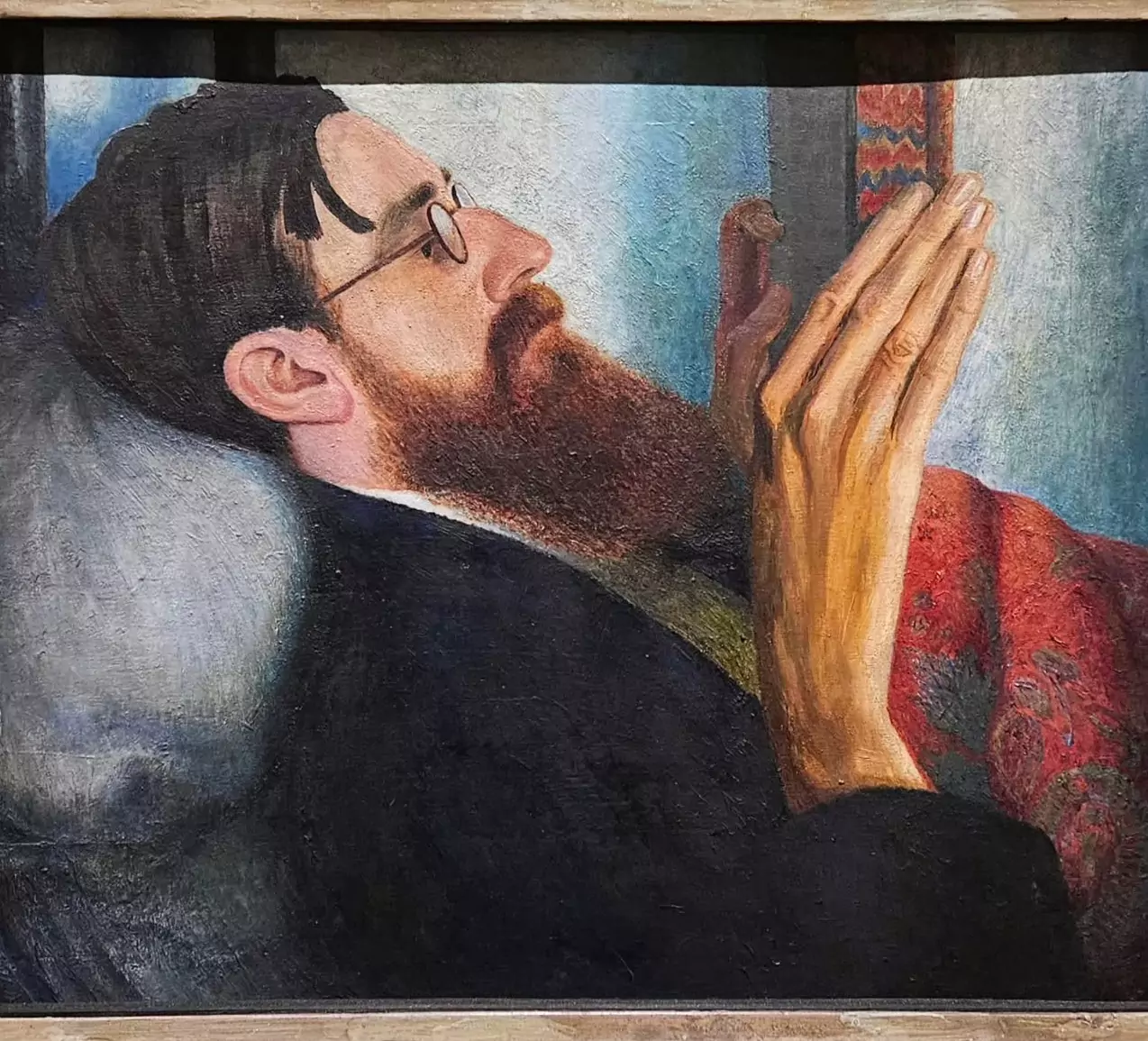

Title: Lytton Strachey (1880-1932), Critic and biographer; son of Sir Richard Strachey.

Date: 1916 Medium/Technique: oil on panel

Dimensions: 20 in. x 24 in. (508 mm x 609 mm)

Location: National Portrait Gallery, London

Standing before Portrait of Lytton Strachey (1916), you can almost hear the quiet hum of intellectual conversation, the flickering intensity of an unusual yet deeply devoted companionship. Dora Carrington, an artist whose name was often eclipsed by her more famous Bloomsbury contemporaries, created something profoundly intimate here—not just a portrait, but a quiet revelation of love, longing, and the complexities of human connection.

Carrington: An Artist Defined by Defiance

In 1910, she went to the Slade School of Art in central London where she subsequently won a scholarship and several other prizes; her fellow students included Dorothy Brett, Paul Nash, C. R. W. Nevinson and Mark Gertler. All at one time or another were in love with her, as was Nash’s younger brother John Nash, who hoped to marry her.

During 1912, Carrington attended a series of lectures by Mary Sargant Florence on fresco painting. The following year, she and Constance Lane completed three large frescoes for a library at Ashridge in the Chilterns. Plans, with John and Paul Nash, for a cycle of frescoes for a church in Uxbridge near London came to nothing with the start of the War. After graduating from the Slade, although short of money, Carrington stayed in London, living in Soho with a studio in Chelsea. Her paintings were included in a number of group exhibitions, including with the New English Art Club, and she stopped signing and dating her work. In 1914 Carrington’s parents moved to Ibthorpe House in the village of Hurstbourne Tarrant in Hampshire, and shortly afterwards she moved there and set up her studio in an outbuilding.

Carrington never quite fit neatly into the art world of her time. She was neither fully an Impressionist nor a Modernist, and she certainly didn’t care to be labeled. She painted what she felt, what she saw, and often, what she couldn’t quite say. Her reluctance to exhibit and her devotion to her own private world—one centered largely around Lytton Strachey—meant that for decades, her art was overlooked. But in Portrait of Lytton Strachey, her genius is impossible to ignore.

A Portrait Charged with Emotion

Here, Strachey sits in repose, draped in an air of thoughtfulness, his elongated face and signature auburn beard making him instantly recognizable. But there’s something more—something deeper—beneath Carrington’s brushstrokes. This isn’t just a likeness; it’s an intimate meditation on a man she adored, despite the impossibilities of their love.

The background is muted, allowing Strachey’s presence to dominate. His hands, expressive and elegant, rest with a delicate unease, capturing the quiet eccentricity that made him both enigmatic and endearing. Carrington’s color choices are understated but deliberate—the earthy tones evoke a sense of warmth, but also melancholy, as if she knew, even then, that this moment in time was fleeting.

A Love That Defied Categories

Carrington and Strachey’s relationship was unconventional, confounding, and utterly sincere. She loved him with an intensity that defied reason, while he—openly gay and devoted to his own emotional freedoms—loved her in return, though not in the way she might have wished. They were inseparable, bound not by passion but by an understanding so rare that it overrode convention.

This portrait, painted with the kind of tenderness only deep familiarity allows, speaks of that love. Strachey isn’t framed as the acerbic critic or the celebrated writer; he is simply himself, as Carrington saw him—an irreplaceable presence in her life, captured with quiet reverence.

On the day she agreed to marry Ralph Partridge she wrote to Strachey, who was in Italy, what has been described as one of the most moving love letters in the English language.

She wrote:

“I cried last night Lytton, whilst he slept by my side sleeping happily — I cried to think of a savage cynical fate which had made it impossible for my love ever to be used by you.”

Strachey wrote back:

“You do know very well that I love you as something more than a friend, you angelic creature, whose goodness to me has made me happy for years, and whose presence in my life has been and always will be, one of the most important things in my life.”

What makes Portrait of Lytton Strachey so compelling is that it is, at its core, a portrait of devotion. It reminds us that love is not always straightforward or reciprocated in expected ways, yet it can still be profound, still be transformative. Carrington’s brushstrokes carry the weight of that understanding, ensuring that Strachey—and the peculiar, beautiful love they shared—will never fade into obscurity.

In the end, this painting is not just a study of a man; it is a study of feeling, of an unspoken connection woven into paint, enduring long after both artist and subject have gone.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!