Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

Text by Vincent DeLuise Author, Educator, Musician at amusicalvision.blogspot.com, Cultural Ambassador, Waterbury Symphony Orchestra

| Artist | Pieter Bruegel the Elder |

|---|---|

| Title | The Blind Leading the Blind |

| Year | 1568 |

| Type | Distemper on linen canvas |

| Dimensions | 86 cm × 154 cm (34 in × 61 in) |

| Location | Museo di Capodimonte, Naples |

In one of my lectures on visual perception and the arts, I have a section devoted to Eye Disease in Art.

An iconic pictorial example in this theme is Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s monumental and poignant, “The Blind Leading The Blind.” (also known as “The Parable of the Blind”). This 1568 painting is a jewel of the wondrous and underappreciated Museo Nazionale di Campodimonte, in Napoli, a must visit in that Baroque gem of a city.

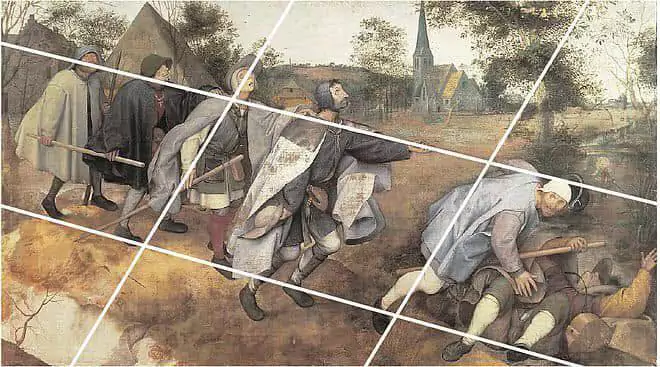

This great painting is fascinating on many levels. Bruegel’s level of precise and accurate observation is almost microscopic in detail. He depicts the six visually impaired protagonists and their raiments within a relatively narrow chromatic palette where browns and greys predominate. The sky too is cloudy and grey. The diagonal composition reinforces the haphazard movement of the six figures as they cascade forward and down into the ditch falling in.

The painting is a Renaissance example of moving pictures. Bruegel demonstrates mastery of foreshortening in depicting the leader of the blind men.

Holding shared walking sticks, six blind men are shown at the moment when their leader stumbles into a ditch. Soon the others will also fall, which the artist conveys by painting the figures along a slanted diagonal. The five standing men are painted with their faces turned up since they rely on their sense of hearing. Each is accurately depicted with a distinct form of blindness. The landscape is also realistic and represents the village of Sint-Anna-Pede near Brussels.

The Blind Leading the Blind is an adaptation of Christ’s parable saying that when the blind lead the blind, they shall fall into a ditch (Matt. 15:14; Lk. 6:39). The painting is also a visual and verbal pun: within this illustrated parable, the downward sloping movement of the figures suggests a parabola—the mathematical term for an arch-shaped curve. Bruegel is justly famous for these subtleties, which entertained the highly educated viewers in the artist’s humanist circles.

Professor of Ophthalmology Zeynel Karcioglu, then at Tulane University, has analyzed this masterpiece, identifying in each man a different ocular condition:

“The first man’s face is not visible; the second twists his head as he falls, perhaps to avoid landing face-first. The third man, on his toes with knees bent and face to the sky, shares a staff with the second, by which he is being pulled down. The others have yet to stumble, but the same fate is implied.”

“The first man’s eyes are not visible; the second has had his eyes removed, along with the eyelids: the third suffers from a whitish corneal scar called a leukoma; the fourth displays atrophy of the globe; the fifth is blind and photophobic; and the sixth has either pemphigus or bullous pemphigoid.”

Ekphrasis

When I teach the medical students and ophthalmology residents this painting, I point out that it goes full circle with the world of medicine as Dr. William Carlos Williams, the pediatrician and poet, wrote an elegiac and ekphrastic poem about the Brueghel painting when he visited the Capodimonte in Napoli.

The term Ekphrasis means “description” in Greek.

An ekphrastic poem is a “vivid description of a scene or, more commonly, a work of art. Through the imaginative act of narrating and reflecting on the “action” of a painting or sculpture, the poet may amplify and expand its meaning.” (Poetry Foundation).

“The Parable of the Blind” by William Carlos Williams

This horrible but superb painting

the parable of the blind

without a red

in the composition shows a group

of beggars leading

each other diagonally downward

across the canvas

from one side

to stumble finally into a bog

where the picture

and the composition ends back

of which no seeing man

is represented the unshaven

features of the des-

titute with their few

pitiful possessions a basin

to wash in a peasant

cottage is seen and a church spire

the faces are raised

as toward the light

there is no detail extraneous

to the composition one

follows the others stick in

hand triumphant to disaster

How wonderfully appropriate for a physician to wax lyrically on a painting, demonstrating the wondrous nexus between medicine and the humanities, to wit, a physician crafting a poem about a painting that depicts disease.

The church in the background has been identified as St-Anna Pede, and the village as the community of Dilbeek on the outskirts of Bruxelles.

The historians Hagen and Hagen, in their book, _What Great Paintings Say_, state that the church in the background, (identified in comments above as the Sint-Anna Church at Dilbeek in modern Belgium) has several meanings:

“One view holds that the church is evidence of the painting’s moralistic intent—that while the first two blind men stumble and are beyond redemption, the other four are behind the church and thus may be saved.

“Another interpretation has it that the church, with a withered tree placed before it, is an anti-Catholic symbol, and that those who follow it will fall following a blind leader as do the men in the ditch.

“Others deny any symbolism in the presence of the church in the painting, noting that churches frequently appear in Bruegel’s village scenes as they were a common part of the village landscape.”

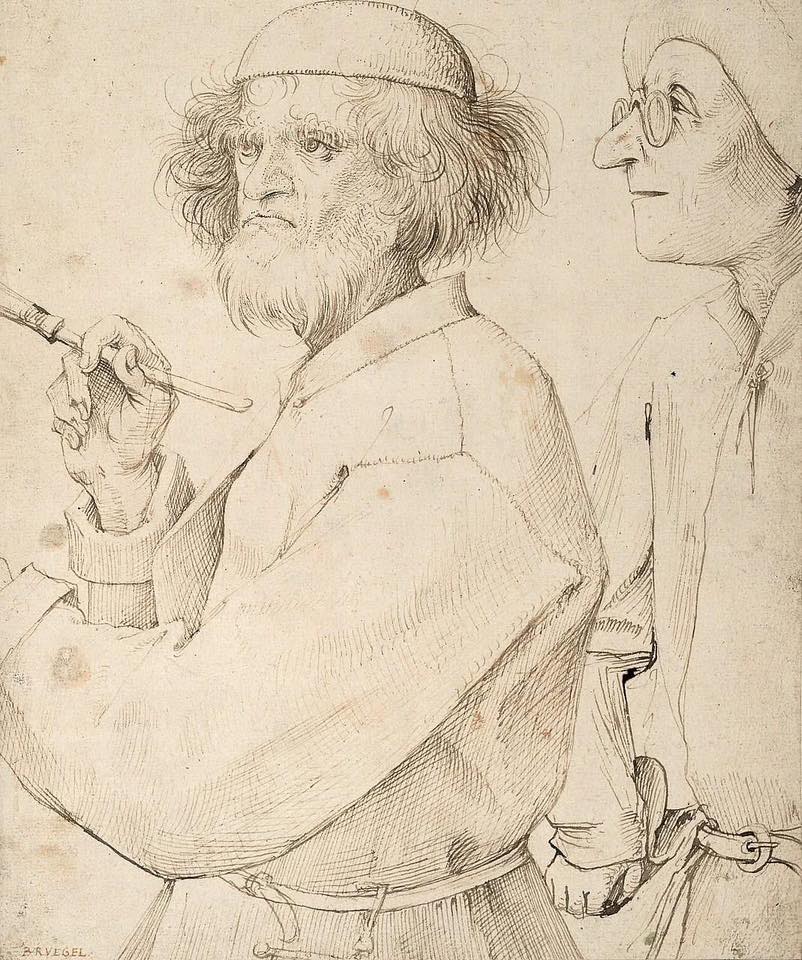

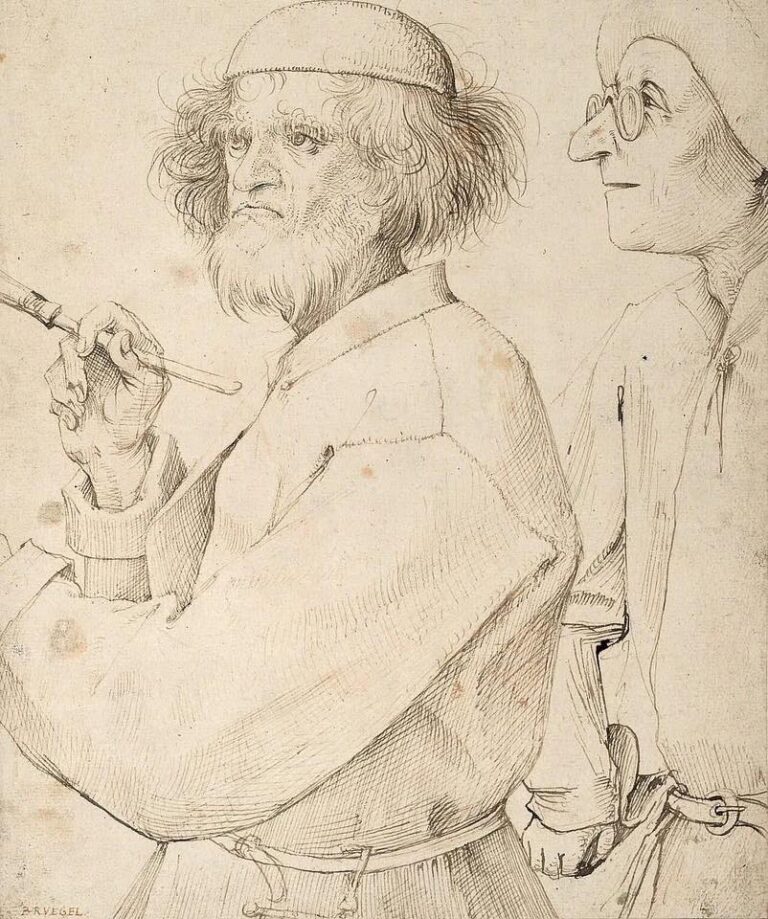

The Met’s Nadine Orenstein states that this drawing “The Painter and The Connoisseur” from c. 1565, is possibly a self-portrait of Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

If it is a self-portrait, note how Bruegel the Elder cuts out his right hand and leaves it out of the pictorial space, and places the paint brush in his left hand.

Pierre Lanthony (J French Ophthalmol Society 1989) has discussed this as one of several ways artists dealt with their hands in self-portraiture

After 1559, Pieter Brueghel the Elder dropped the letter “h” in his last name and began spelling it as “Bruegel.”

Since this painting, The “Blind leading the Blind,” is dated 1568, I have chosen the Pieter Bruegel orthography without the letter “h” to align with the artist’s choice.

References:

1) Rose-Marie Hagen and Rainer Hagen. _What Great Paintings Say_. Taschen publishers. 2003

2) Zeynel Karcioglu. Ocular Pathology in The Parable of the Blind Leading the Blind and Other Paintings by Pieter Bruegel”. Survey of Ophthalmology. 47 (1): 55. January 2002

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!