Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

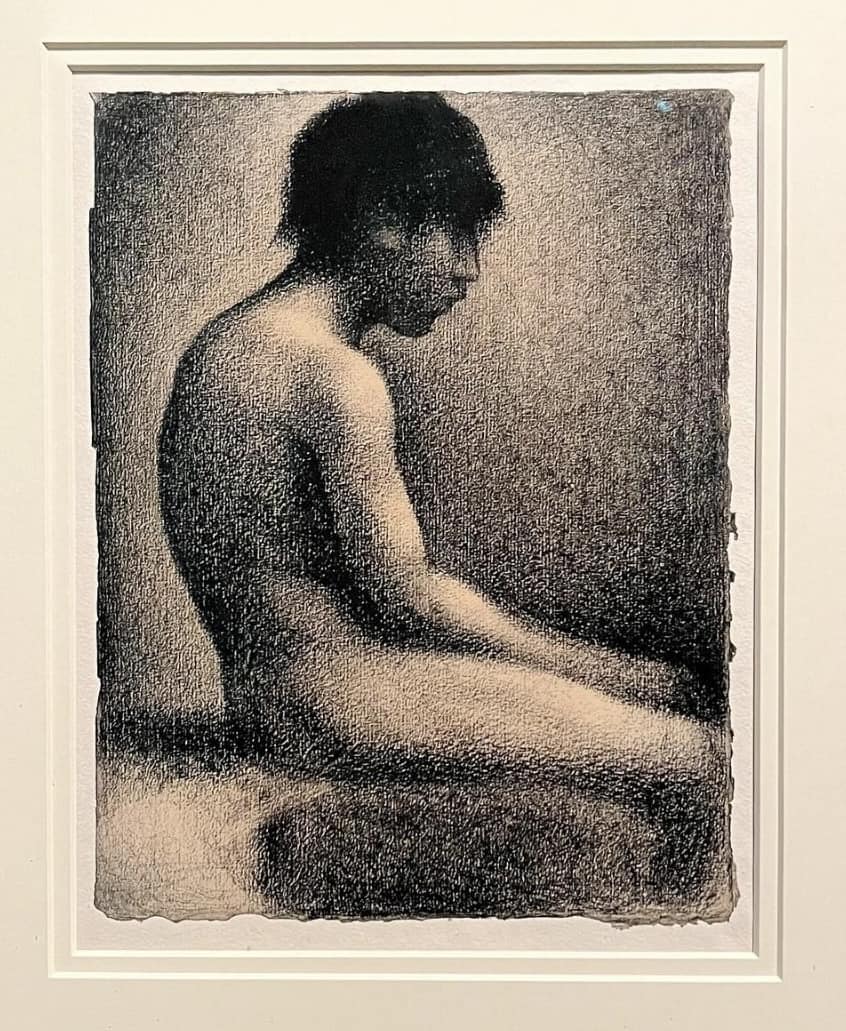

Georges Seurat, Study for Bathers at Asnières, 1884

- Artist: Georges Seurat

- Title: Study for Bathers at Asnières

- Year: 1884

- Medium: Conté crayon on paper

There is a particular stillness in Seurat’s Study for Bathers at Asnières. The young man, stripped of all distractions, sits quietly, lost in thought. His form, bathed in light, emerges from a haze of meticulously built-up tonal layers. There is no rush here, no flickering spontaneity of an Impressionist moment. Instead, Seurat gives us something profoundly considered—his mastery of light, form, and atmosphere distilled into a single figure.

This drawing is not just a study for a larger work; it is a quiet manifesto. It speaks of Seurat’s obsession with structure, his scientific approach to perception, and his radical departure from the Impressionist tradition. With nothing but conté crayon and paper, he sculpts a world where light and shadow become tangible, and where even the subtlest gradation in tone carries weight.

A Study Unlike Any Other

What makes this work so striking is its self-sufficiency. Unlike many preparatory sketches, which serve only as blueprints, this study holds its own as a complete work of art. The figure is fully formed, its anatomy carefully articulated through shadow and light. Seurat’s signature softness is present, yet his precision remains intact. Every contour is carefully thought out, every transition from dark to light expertly controlled.

This isn’t a casual sketch dashed off in the moment. It’s a carefully calibrated exercise in control, an attempt to understand how light defines form, how shadows breathe life into volume. Seurat doesn’t outline; he lets the image emerge gradually, built from a delicate interplay of values.

Seurat’s Sculptural Approach to Drawing

Seurat’s technique here is nothing short of masterful. Using conté crayon—a dense, rich medium ideal for achieving deep blacks and subtle shading—he constructs his image as if he were carving it out of stone. His method is almost sculptural, with shadows behaving like chisel marks, defining the solidity of the figure’s body.

Rather than relying on hatching or cross-hatching, Seurat employs a method closer to sfumato, where tonal gradations create an effect of atmosphere and depth. The background melts away into a diffuse darkness, reinforcing the presence of the seated figure. This is where his brilliance lies: in the ability to suggest weight and volume with nothing but a carefully orchestrated range of values.

The Bather’s Posture and Expression

The figure, seated and gazing downward, exudes a profound sense of calm. There is no interaction, no narrative urgency. His body is relaxed but not slack—his posture suggests a moment of contemplation rather than exhaustion. Unlike the final painting, where the bather is part of a larger social scene, here he exists in solitude, as if caught in an intimate, private moment.

This small shift in focus reveals something essential about Seurat’s process. He wasn’t just refining the composition; he was exploring mood, psychology, and the subtle ways in which posture and light shape emotion. This figure is no longer just a component in a grander design—he is a presence in his own right, carrying the weight of the composition entirely on his shoulders.

From Sketch to Masterpiece

Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières (1884) would go on to become one of the defining works of the Neo-Impressionist movement. But before it could take its final form, Seurat devoted himself to an exhaustive series of studies, refining every element, every pose, every interaction of light and shadow.

This study represents a crucial step in that process. Here, we see the bather in near-final form, his proportions, gestures, and lighting already resolved. What remains is the transformation from monochrome to color, from conté crayon to the radical new language of Divisionism.

What’s fascinating is how much of the final painting is already present in this study—not just in terms of form but in the underlying philosophy. Seurat’s scientific rigor, his emphasis on structure, his careful balancing of light and shadow—all of these elements would later manifest in his Pointillist technique. The difference is that here, without the complexity of color, we can see the fundamental architecture of his vision laid bare.

Breaking Away from Impressionism

At the time of this drawing, Seurat was moving decisively away from Impressionism. While Monet, Renoir, and their contemporaries sought to capture fleeting moments with rapid, broken brushstrokes, Seurat was after something far more deliberate. He didn’t want to capture an instant; he wanted to construct an image that would last.

This study embodies that shift. There’s a timeless quality to it, a stillness that sets it apart from the buzzing light and movement of Impressionist works. The figure isn’t caught in a moment of action; he is placed, solid and unmoving, within a carefully composed world.

It’s a vision that owes more to classical sculpture than to the spontaneity of Impressionist painting. And yet, despite its careful construction, there is nothing rigid about this figure. The softness of Seurat’s shading, the atmospheric quality of his light, imbue the drawing with a quiet, living presence.

The Legacy of Seurat’s Studies

What Seurat achieved in his preparatory works was nothing short of revolutionary. He didn’t just use studies to refine his compositions—he used them to explore the very nature of perception, light, and structure.

His methods would go on to influence generations of artists, from the Divisionists to the Cubists, who saw in his careful planning and structural approach a bridge between traditional draftsmanship and modern abstraction. Paul Signac, Seurat’s closest collaborator, would later push these ideas even further, transforming the study of light and color into a fully developed movement.

Even today, Seurat’s studies continue to fascinate scholars and artists alike. They reveal not just the mechanics of his process but the depth of his vision—his insistence that art could be both rigorously constructed and deeply expressive.

Looking at this drawing, one can’t help but admire the quiet intensity of Seurat’s craft. There is a reverence for form here, a devotion to the subtle interplay of light and shadow that elevates this work beyond mere preparation. It is a piece that stands on its own, offering a glimpse into the mind of an artist who saw the world not just as a collection of fleeting impressions, but as something structured, ordered, and profoundly beautiful.

In Study for Bathers at Asnières, we see Seurat in his purest form—patient, precise, and endlessly searching for the perfect balance between science and art. And in that search, he created something timeless.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!