Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

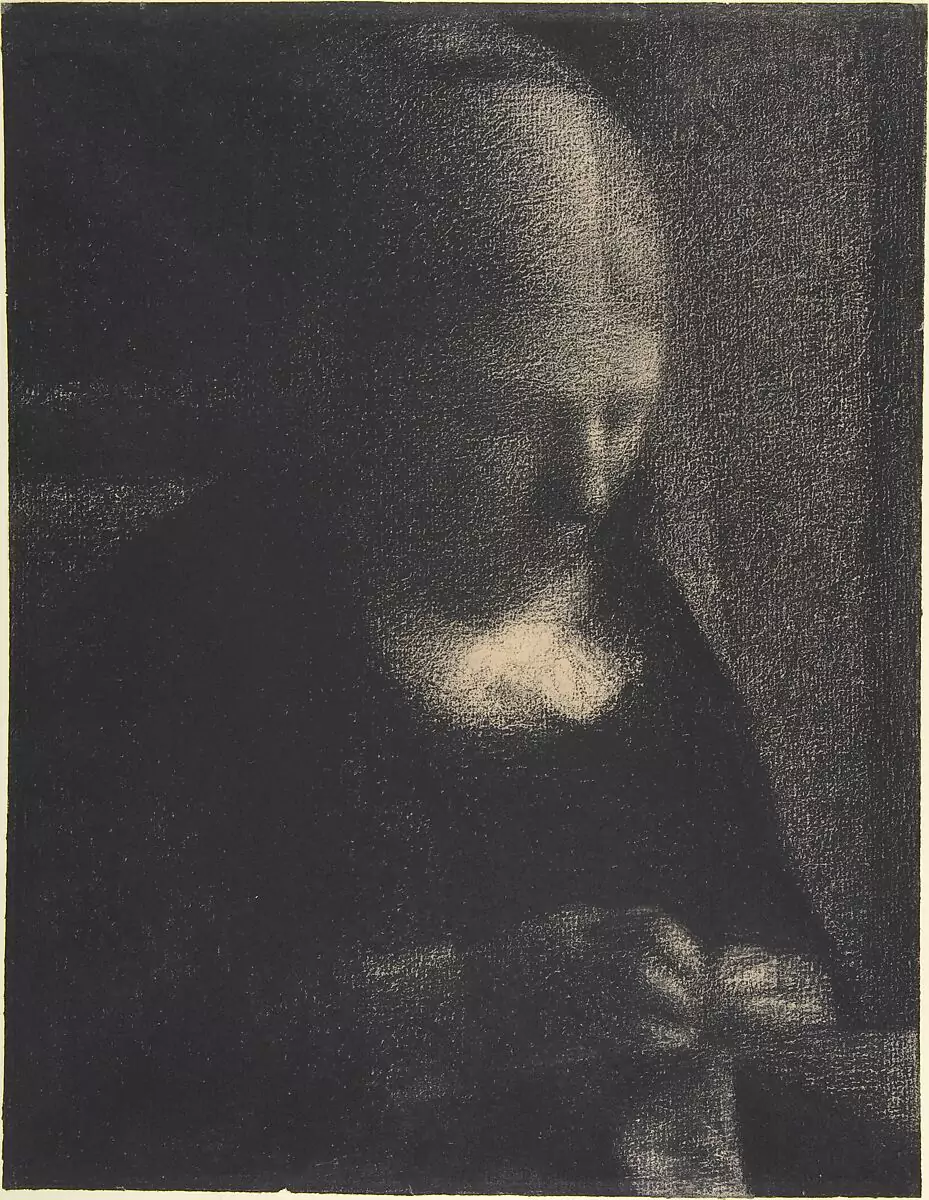

Artist: Georges Seurat (French, Paris 1859–1891 Paris)

Title: Embroidery; The Artist’s Mother

Date: 1882–83 , Medium: Conté crayon on Michallet paper

Dimensions: 12 5/16 x 9 7/16 in. (31.2 x 24.1 cm)

Collection : The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This tranquil portrait of the artist’s mother, Ernestine Faivre, is a tour de force of modeling in Conté crayon, Seurat’s favorite graphic medium. The work is drawn entirely without line in tonal passages of velvety black. Scarce atmospheric light, subtly evoked by lessening pressure on the crayon, illuminates the interior where the woman sews, creating a serene ambiance of quiet domesticity. The abstract beauty achieved in such works earned the praise of fellow artist Paul Signac, who called them “the most beautiful painter’s drawings that ever existed.”

Seurat’s Charcoal Works as a Visual Vignette

Seurat’s charcoal works are not just studies in technique; they are also a window into his artistic process and his deeper exploration of the human figure and environment. When viewing his charcoal works up close, the texture of the strokes is evident, and the marks appear raw and expressive. However, when viewed from a distance, the subtle interplay of light and shadow becomes apparent. The image transforms, and the viewer is presented with a vignette of the subject as if seen through a slightly out-of-focus lens. This visual effect is a result of Seurat’s use of layering and hatching, which builds up texture and tone while allowing for smooth transitions between light and dark areas.

What is remarkable about Seurat’s charcoal works is that they often give the impression of being illuminated from within. Unlike traditional drawings, where the light is often created through erasure or white space, Seurat’s charcoal pieces use the marks themselves to create the illusion of light. By varying the pressure applied to the crayon or charcoal, Seurat could create subtle shifts in tone, simulating the effects of natural light on the surface of his subjects. This allowed him to capture the nuances of shadow and light in a way that felt almost photographic, lending his works a modern sensibility that would later influence movements like Impressionism and even early photography.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!