Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

Throughout art history, the illusion of movement has been a pursuit of artists seeking to transcend the static nature of their medium. Yet, in the 20th century, a radical idea took form: what if art could truly move? What if it could incorporate real motion as an intrinsic part of its expression? Thus emerged Kinetic Art, a groundbreaking movement that reshaped the boundaries of artistic creation and perception.

The Origins of Kinetic Art – Breaking Free from the Static

Kinetic Art, as a formalized movement, can be traced back to the early decades of the 20th century, but its roots lie even deeper in the artistic avant-garde. One of the earliest proponents of movement in art was Naum Gabo, a Constructivist sculptor who, in his 1920 “Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave),” introduced a motorized element to his work. This early experiment signaled the dawn of a new artistic direction where movement was no longer an illusion but a tangible reality.

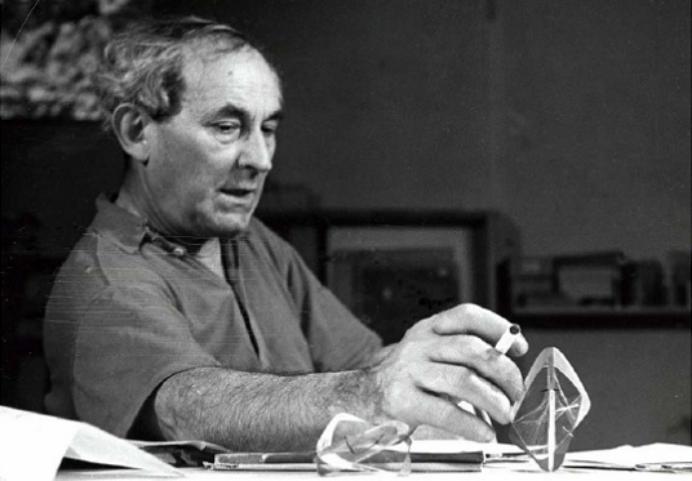

While Gabo’s work was largely theoretical, it was Alexander Calder who popularized the concept of kinetic sculpture through his mesmerizing mobiles. With a delicate interplay of balance, air currents, and mathematical precision, Calder’s mobiles were suspended orchestrations of motion, constantly shifting with the environment. Unlike mechanical movement, Calder’s works embodied an organic fluidity that transformed the static nature of sculpture.

As the 20th century progressed, artists continued to explore movement through diverse approaches. The Bauhaus school, particularly with figures like László Moholy-Nagy, emphasized the use of technology and light to create dynamic compositions. Meanwhile, the Italian Futurists, including Umberto Boccioni, sought to depict speed and dynamism in their paintings and sculptures, capturing a world in flux.

A Movement in Motion – The Rise of Kinetic Art

By the 1950s and 1960s, Kinetic Art had solidified into a recognized movement, with artists experimenting not just with motion, but also with audience participation. A key exponent of this period was Jean Tinguely, whose chaotic, self-destructive machines introduced an element of unpredictability. His infamous “Homage to New York” (1960), a sculpture designed to destroy itself, challenged traditional notions of permanence in art.

Simultaneously, Op Art, a movement closely linked to Kinetic Art, utilized optical illusions to create the sensation of movement. Artists like Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley played with geometric patterns and color contrast to create vibrating, pulsating effects that engaged the viewer’s perception in an almost kinetic manner.

One of the most iconic exhibitions that propelled Kinetic Art into the mainstream was the 1955 Le Mouvement exhibition at Galerie Denise René in Paris. This landmark show featured artists like Calder, Vasarely, Tinguely, and Moholy-Nagy, all of whom demonstrated different facets of motion in art. It was here that the term “Kinetic Art” was popularized, signaling the arrival of a movement that sought to bridge the gap between art, science, and technology.

The Science and Philosophy Behind Kinetic Art

At its core, Kinetic Art is deeply intertwined with scientific principles, particularly physics, mathematics, and engineering. Artists working in this movement had to consider aspects such as balance, momentum, and light reflection. Jesús Rafael Soto, for instance, crafted works that required the viewer’s movement to activate their full effect, blending art with perceptual psychology.

Moreover, Kinetic Art posed profound philosophical questions about the nature of reality and time. Traditional art forms captured a moment; kinetic works unfolded across time. In a way, these artworks lived and breathed, engaging with external forces and never appearing the same twice. This interactivity led to the rise of “participatory art,” where the viewer was no longer a passive observer but an active participant in the creation of meaning.

Notable Artists and Masterpieces

- Alexander Calder (1898-1976) – Known for his mobiles, such as “Lobster Trap and Fish Tail” (1939), Calder redefined sculpture as a dynamic, constantly changing entity.

- Jean Tinguely (1925-1991) – His self-destructing “Homage to New York” (1960) was an anarchic commentary on the ephemeral nature of art and society.

- Victor Vasarely (1906-1997) – A pioneer of Op Art, Vasarely’s works like “Zebra” (1937) trick the eye into perceiving movement.

- Jesús Rafael Soto (1923-2005) – His “Penetrables” series blurred the line between artwork and viewer, allowing audiences to walk through kinetic installations.

- Yaacov Agam (b. 1928) – A leading figure in “transformable art,” Agam’s pieces change based on the viewer’s angle, creating an ever-evolving experience.

Kinetic Art in the Contemporary World

Although Kinetic Art flourished in the mid-20th century, its legacy continues in contemporary art. Modern artists integrate digital technologies, AI, and robotics to push the boundaries of movement in art.

For instance, artists like Theo Jansen create Strandbeests, wind-powered kinetic sculptures that mimic the locomotion of living organisms. Meanwhile, in digital art, kinetic principles are explored through interactive installations, such as teamLab’s immersive environments, where the motion of the audience affects the surrounding visuals.

The influence of Kinetic Art is also evident in architecture and design. The Centre Pompidou in Paris, with its exposed mechanical systems, echoes the movement’s embrace of visibility in structure. Similarly, the kinetic facades of contemporary skyscrapers incorporate movement-responsive elements, blurring the lines between function and aesthetics.

The Ever-Moving Spirit of Art

Kinetic Art is more than just a genre or movement—it is a philosophy that celebrates the ephemeral, the unpredictable, and the interactive. In a world increasingly driven by motion and technology, Kinetic Art remains as relevant as ever, continuing to inspire artists, architects, and designers to rethink the very nature of artistic expression.

As we witness the continuous evolution of art in the digital era, one thing remains clear: the poetry of motion, once an ambitious artistic dream, has become an undeniable reality. And in this ceaseless dance of light, form, and energy, Kinetic Art ensures that art itself never truly stands still.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!

![Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, 1939, Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York]](https://artaddictgalleria.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Lobster-Trap-and-Fish-Tail-1939-Museum-of-Modern-Art-New-York.-©-2018-Calder-Foundation-New-York-Artists-Rights-Society-ARS-New-York-768x768.webp)