Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

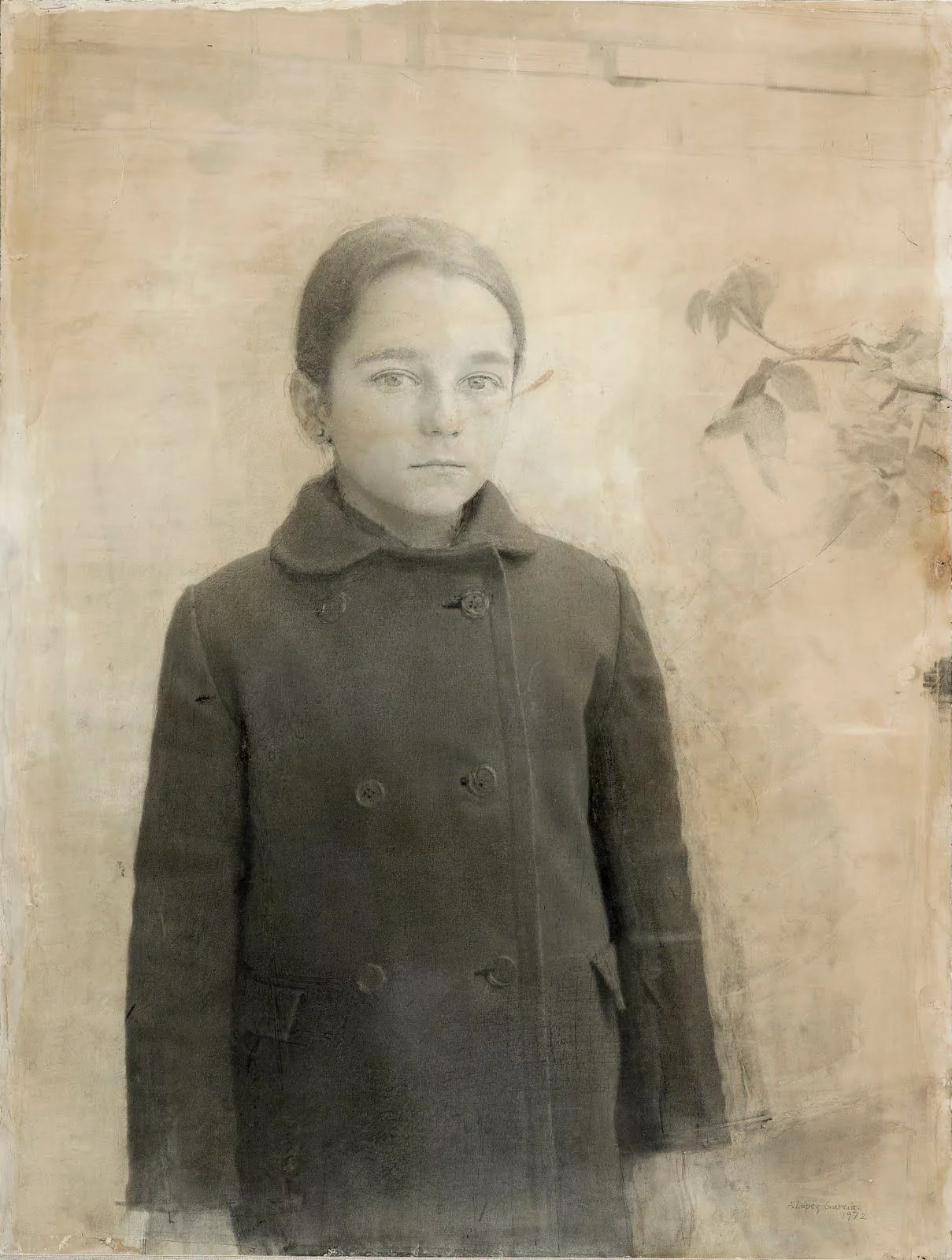

| Artist | Antonio López García |

|---|---|

| Title | María |

| Year | 1972 |

| Medium | Pencil on Paper |

| Dimensions | 70 x 53.3 cm |

| Location | Private collection |

You pause when you see María, even though it’s just pencil on paper. It feels familiar, soft, uncanny. That coat—folded up tight, buttoned all the way to the neck—sparks a memory. You might have worn the same one when you were ten. Maybe even your own coat is folded in your mind right now. Antonio López has painted a time that belongs to all of us.

He drew his daughter María around autumn 1972, when she was ten years old. It’s an unfinished portrait, and that’s part of its quiet power. The background melts into nothing. Her hands and parts of her face seem to fade, like memory slipping. López didn’t chase detail everywhere. He held back in places, offering you space to feel, not just look.

López is a master of hyperrealism, trained in Madrid’s prestigious academy. His attention to reality emerges slowly, patiently. He doesn’t work from photographs—he draws from life. Days may pass in a single session as the model purses her lips, shifts her hair, or sighs. And because the model is his daughter, there’s a different rhythm here. María got tired. She needed breaks. And the drawing stopped. But that pause left something beautiful.

Look at the coat. López renders fabric folds with a quiet reverence. That wool, so thick and boundary-setting, becomes almost a barrier between girl and world. And yet, her eyes are soft, half-guarded, somewhere between a child refusing to keep a pose and someone asking you to catch her secret.

That invisibility—hands blurred, the environment erased—makes it timeless. You’re not just seeing a ten-year-old in 1972. You’re seeing childhood itself—fleeting and present at once. That conflict between clarity and blur nudges at memory’s edge: you recall her eyebrows, you recall winter mornings, you recall wanting to go inside where it’s warm.

Something else: art students sometimes judge unfinished work as incomplete. But López invites it as a mirror. Have I ever noticed how unfinished my own memories feel? Have I ever seen time vanish from a portrait I thought I understood?

It’s stirring. Because the portrait whispers of absence. María’s parents grow old. Children grow taller. I’m here, viewer, chasing memory inside a single sketch.

Here’s a small but telling detail: the buttons. All done up, tight. That was how we bundled up against cold when we were children. That’s how we said “I’m safe—but I’m fragile.” López didn’t overstate it. In that tiny touch lives an entire childhood.

I think of how few artists captured children like that—just children being. No saintly halos. No grand themes. Just a coat, a gaze, a little girl who needed to stop posing.

When you step back, the portrait softens but stays steady. Unfinished but unchanged. If those hands aren’t drawn, it’s not a failure—it’s a space for you to breathe, to wonder what she was thinking, what López was feeling when she finally rested.

Maybe he felt relief. Maybe love. Maybe sorrow that time was slipping. He let María walk away from sitting still, and gave us a drawing that holds both presence and absence. A quiet grace, something rare, something human.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!