Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

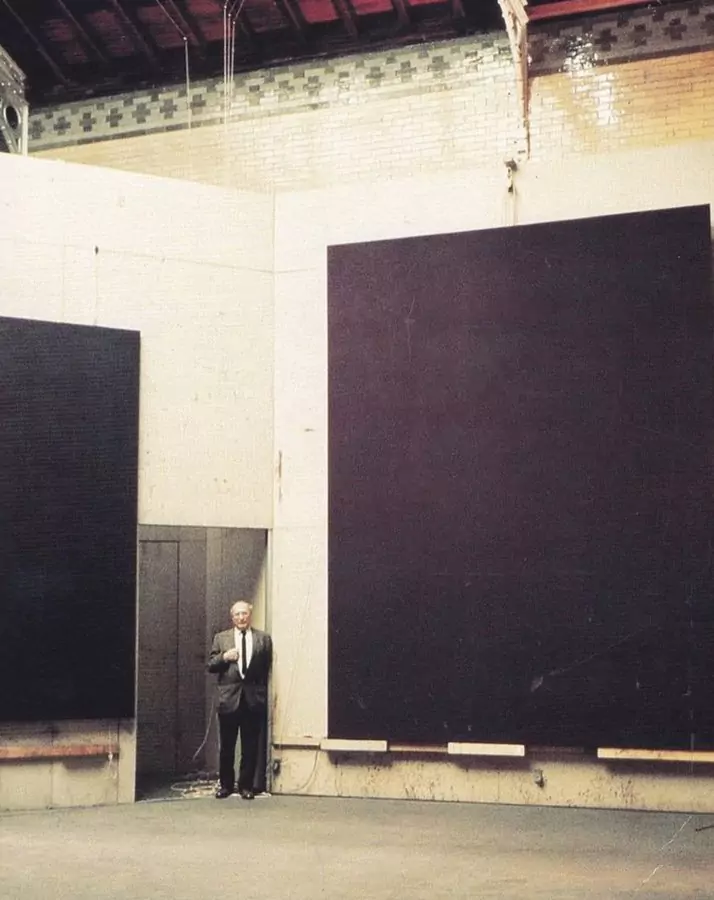

There is something unnerving about standing in front of a Mark Rothko painting. It’s not just the size—though his towering canvases do have a way of making you feel like a trespasser in their presence. It’s the weight of them, the sheer density of color, as if something vast and unfathomable is pressing against you. And then there’s the silence. Rothko’s paintings don’t shout, they don’t explain. They loom, they hover, they demand.

“I became a painter because I wanted to raise painting to the level of poignancy of music and poetry.” Mark Rothko

Rothko’s art is often mischaracterized as serene, meditative even. But there is nothing peaceful about these paintings. They pulse with tension, built layer by layer in thin washes that absorb light rather than reflect it. His reds smolder. His blacks threaten. Even the brightest hues are laced with something ominous, as if his colors carry the memory of their own disappearance. Rothko was a man consumed by darkness, and it seeps into his work at every turn.

Born in 1903 in what is now Latvia, Markus Rothkowitz arrived in America as a child, his family fleeing anti-Semitic violence. The trauma of exile, the burden of being an outsider, never left him. He studied, he struggled, he painted, but the art world was not yet ready for what he had to offer. His early work wrestled with figuration—somber, weighty compositions that owed as much to Matisse as they did to his own immigrant experience. But something wasn’t clicking. It wasn’t until the 1940s, when he began stripping away everything extraneous, that Rothko found his true language. Figures dissolved into floating planes of color, narrative gave way to atmosphere. He had arrived.

By the time he reached his peak in the 1950s, Rothko’s paintings had become something like religious icons for the secular age. He despised the label “abstract expressionist” and bristled at any attempt to reduce his work to mere aesthetics. These were not paintings to be “liked” or “disliked.” They were experiences. He insisted his viewers stand close—mere inches away—so that the fields of color would envelop them completely. And they do. Stand before a Rothko, really stand there, and you’ll find that the edges dissolve, your own body disappears. You are somewhere else.

But for all their grandeur, there is something deeply intimate about Rothko’s works. He spoke of them as dramas, of the colors as actors engaged in conflict. You can feel that struggle in every brushstroke. The edges of his shapes tremble, their borders are never fixed. The layers underneath always threaten to surface, ghosts of earlier decisions left unresolved.

And then there is the black. Rothko’s later works, especially the Seagram Murals and his final paintings, are suffocating in their darkness. These aren’t just paintings; they are spaces, voids, thresholds. The Seagram Murals, commissioned for a lavish New York restaurant Rothko ultimately refused to deliver them to, are soaked in reds so dark they are nearly black, windows onto some realm beyond knowing. And then, finally, came the true darkness—the Black on Gray paintings, the ones he made as his body failed him, as the world narrowed. These are his last words. Thin, trembling bands of black over gray, as if light itself had drained away.

Rothko took his own life in 1970, a few months before his paintings found their way to the Rothko Chapel in Houston, one of the most haunting spaces in modern art. It is impossible not to see his end in his final works, but to reduce them to mere suicide notes would be a mistake. Rothko was never painting his own suffering alone. He was reaching for something larger, something shared. His paintings ache with human longing, with the unbearable weight of existence. They are not about death. They are about everything before it.

To stand in front of a Rothko is to stand on the edge of something vast. He doesn’t give answers. He doesn’t tell you what to feel. He only opens the door to the abyss and lets you look.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!