Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

| Artist | Otto Dix |

|---|---|

| Title | Portrait of a Prisoner of War |

| Year | 1945 |

| Medium | oil and tempera on cardboard |

| Dimensions | 82.5 x 67.5 cm |

| Location | Unterlinden Museum, Colmar |

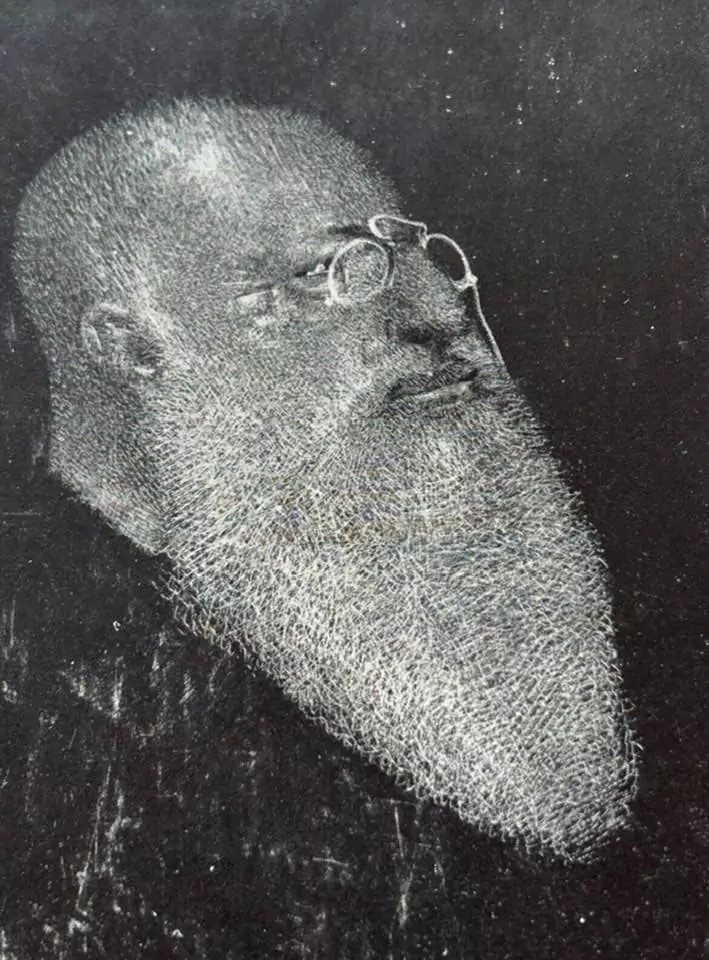

You don’t walk into Otto Dix’s Portrait of a Prisoner of War expecting a flourish of brushwork or a clever trick of light. There’s quiet in the lines of that weary face, a stillness you almost feel breathing. He didn’t paint a hero—he painted a man stripped to his own self, staring out from the canvas like a ghost caught between times and truths. That vulnerability, born from being in a French POW camp near Colmar, is what keeps tugging at you.

Picture Europe during the stretch from 1815 to 1940. After the whirlwind of the Napoleonic wars, something curious took hold – Europe entered a second renaissance, this time fueled by coal, steam, and iron. Across the continent, painting became a kaleidoscope. You had romantic landscapes arguing with academic portraits, realism trading barbs with symbolism, and impressionism dancing alongside secessionist strokes. None of these styles dominated, and intent didn’t belong to a political banner—religion, ideology, nationalism, or socialism. It was messy, brilliant, and totally alive.

That messy plurality created space. Few artists today operate in that kind of freedom. Dix, made brash by the horrors of the trenches in World War I, rode into that chaos armed with etchings depicting dead soldiers up close and ugly—his Der Krieg series shocked Germany into recognition. Fast forward to the 1920s, and Germany was swarming with Weimar absurdity: decadent cabarets, grotesque figures, raw satire—all framed under the banner of New Objectivity. Dix stood side by side with George Grosz, painting society’s griping vein, unfiltered.

Then came the dark turn. The Nazis called him “degenerate,” kicked him out of his teaching job, banned his exhibitions. But Dix couldn’t just vanish—even under surveillance, he refused flattery. He stayed, retreating to Lake Constance and painting allegories and landscapes that disguised something deeper, while his nerve simmered.

And then came 1945. The battles were done, but Dix was dragged into one last fight when he was pressed into the Volkssturm—Germany’s desperate militia. Captured by French forces, he landed in a POW camp in Alsace. But here’s what changed the picture: instead of being silenced, he was set to work. A camp officer, recognizing the name, let Dix paint—small wonders, portraits, even a triptych for the chapel. That chapel nestled in a convent became a place of unmeasured grief and stubborn hope.

One of those paintings was this Portrait of a Prisoner of War. No theatrics, no grand allegory. A bald man, hollowed cheeks, a landscape turned skeletal behind him—or maybe it’s barbed wire and branches. You lean in, and there he is: all fatigue and fleeting dignity. The paint is expressionist, sure—harsh angles, somber tones—but not hyperbolic. He captures that moment when survival morphs into memory, and despair bleeds into acceptance.

That painting anchors what Europe gave artists in the earlier century—from the literary salons of Vienna to the boho clusters of Paris. The freedom to explore idea after idea, form next to form, allowed Dix’s career—even his trauma—to find a language. From neo-classical roots to expressionist angels, surrealist visions, cubist distortions, and fauvist fire, European painting exploded in that time not because it was pretty, but because it had room to breathe.

But that freedom ended. The Nazis imposed one vision, Russia after ’17 demanded one voice. That diversity—of faith and politics, of brushstroke and message—was snapped shut. Dix’s work from the early post-war years, including this grim portrait, became the last bloom in a garden Europe had torn down.

He went on to survive and paint allegories and religious subjects after his release in 1946. He built a legacy recognized in divided Germany, honored by both East and West. But even as landscapes and saints returned to his canvas, that POW portrait held its own weight: a single frame that bridged two eras—one plural, one repressed; one hopeful, one wary.

Standing before it, just as European painting once stood before every new wave, you’re not looking at history—you’re looking through it. And in that glance, maybe that silent plea or internal reckoning, you feel the pulse of a continent that once let its artists wander. The painting asks: can we ever go back? And really, you’re asking back: how could we ever lose that freedom?

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!