Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

There is a certain inevitability to Paul Cézanne. The more one looks at 20th-century painting, the more one circles back to him. Picasso saw it early, calling him “the father of us all.” Matisse reportedly owned one of his Bathers and called it his personal Gospels. And yet, Cézanne never fit neatly into any movement. He was never fully an Impressionist, nor a Post-Impressionist in the same way Van Gogh or Gauguin were. He was something else—a bridge, a rupture, an entirely different language forming within the old.

An Artist in Resistance

To understand Cézanne, one must first recognize his resistance. Resistance to academicism, resistance to the fleetingness of Impressionism, resistance even to the idea of finishing a painting. He famously said, “I want to make of Impressionism something solid and durable, like the art of the museums.” For all his friendships with Pissarro and Monet, he did not share their fascination with momentary light effects. Instead, he sought structure. Mass. An underlying reality beyond surface appearances.

This is where Cézanne’s brushwork becomes revolutionary. He does not blend; he constructs. His paintings are built with deliberate, parallel strokes that form a rhythmic tension. His still lifes—apples, pears, and ginger pots—are not arranged as much as they seem to exist in a kind of precarious harmony, teetering between solidity and instability. Look at The Basket of Apples (c. 1893). The perspective is skewed, the table edges refuse to align, and yet, the composition holds. It breathes. It is unmistakably real, not because it is mimetic but because it is painterly truth.

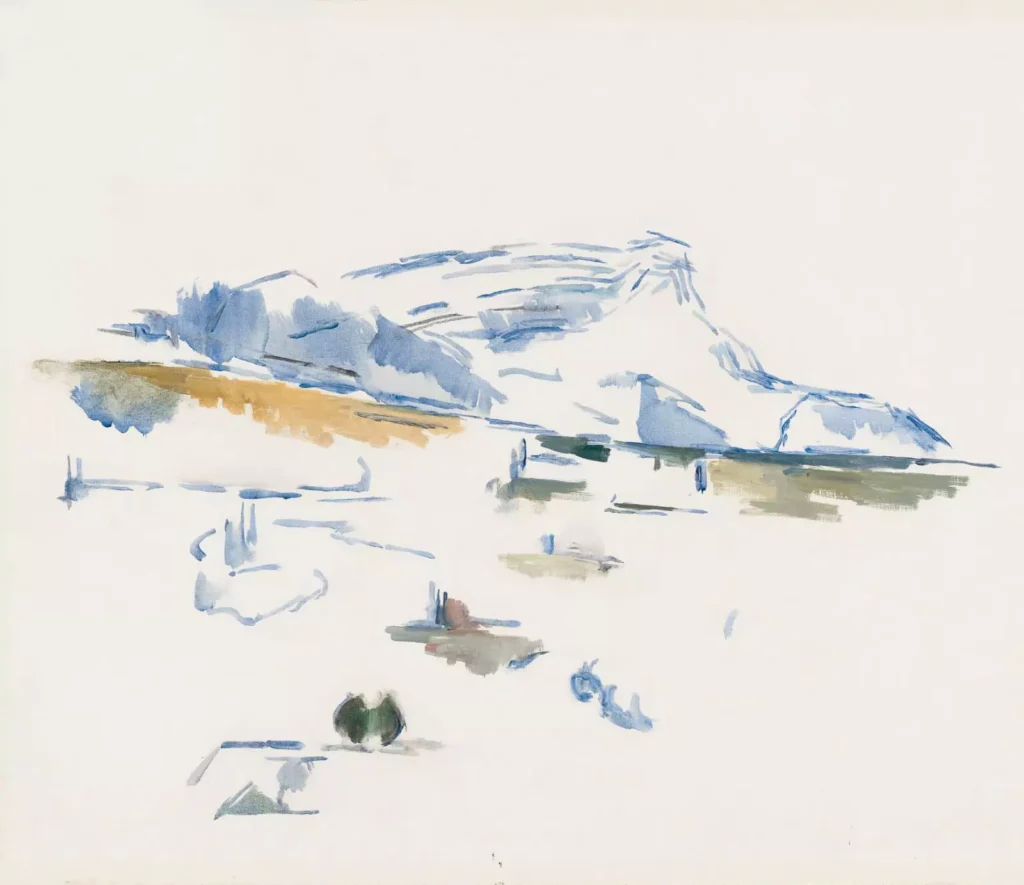

The Mountain That Became a Philosophy

If one painting could summarize Cézanne’s lifelong preoccupations, it is his endless return to Mont Sainte-Victoire. The mountain was not simply a subject; it was a proving ground, a manifesto in landscape form. In his early paintings, it appears almost traditionally rendered, with the sky sitting comfortably above the land. But as the years progress, the boundary between air and earth dissolves. Sky is no longer just a backdrop; it pushes forward, asserting itself as form. The mountain, too, is no longer a singular, static shape. It fractures into geometric planes, foreshadowing Cubism before the term even existed.

What Cézanne does in these paintings is astonishing. He reorders the act of seeing. Perspective, which had long been a construct of Renaissance logic, gives way to a new kind of visual experience. There is no fixed vanishing point; instead, space is assembled through shifting planes of color. This is not the world seen through the lens of a camera; it is the world perceived through movement, through the slow accumulation of looking.

The Weight of Apples, the Gravity of Forms

Cézanne’s still lifes are unlike any before them. Compare his apples to those of Chardin or Courbet—where they painted fruit as objects of lush realism, Cézanne turns them into architectural elements. “Treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone,” he reportedly told a young painter. But this is often misunderstood as simplification. In reality, Cézanne is not reducing nature to geometry; he is revealing its underlying logic.

Consider Still Life with Plaster Cupid (c. 1895). The objects seem caught in an unstable push and pull, as if space itself is being negotiated. The Cupid figure, sculpted and fixed, stands in contrast to the shifting forms around it. Cézanne seems to be questioning permanence—what in an image is fixed, and what is in flux? The answer, always, is both.

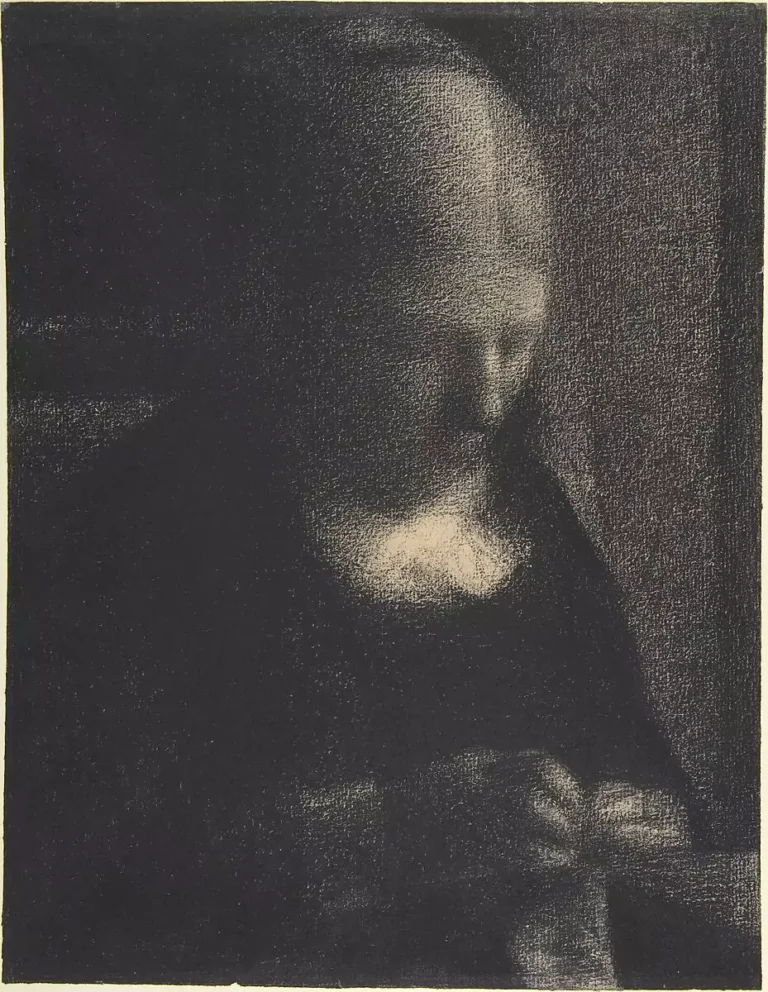

Portraits and the Problem of Presence

Cézanne’s portraits are among his most haunting works. Unlike the psychological depth sought by Rembrandt or Van Gogh, Cézanne’s figures seem withdrawn, almost sculptural in their detachment. His wife, Hortense, was his most frequent subject, yet she often appears more like a still-life element than a person captured in the immediacy of emotion. In Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair (c. 1877), she is nearly expressionless, her presence more about color, shape, and weight than individual personality. This has led some to call Cézanne a cold painter, uninterested in human psychology. But perhaps this is a misreading. Cézanne was not painting his wife as a person but as a presence—as something occupying space, with volume and density. His portraits ask us to see not just the sitter but the act of seeing itself.

The Late Work and the Unfinished

Cézanne never stopped working, never stopped questioning. In his later years, his canvases became increasingly fragmented, his forms dissolving yet more firmly constructed. The watercolor sketches of his final years are almost meditative in their looseness, yet they hold the same weight as his denser oil paintings. One can see in these works a path toward abstraction, toward something beyond painting as it had been known.

In 1906, at the age of 67, Cézanne collapsed while painting outdoors, caught in a storm. He died shortly after. His last works remained unfinished, but perhaps that is fitting. Cézanne was always in a state of becoming—his paintings were never about completion but about the ongoing process of seeing, understanding, and reconstructing the world through paint.

To look at a Cézanne today is to experience painting in its purest form. His canvases are laboratories of perception, lessons in how art is not about copying reality but about inventing a way to see. Without him, there is no Cubism, no Fauvism, no modern abstraction. Every brushstroke carries a question: How does space work? How does color create form? What is painting, if not a reordering of experience?

Cézanne still matters because he never gave us easy answers. His paintings demand slow looking, demand that we participate in their making. And in doing so, they remind us why painting—why art itself—remains essential.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!