Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

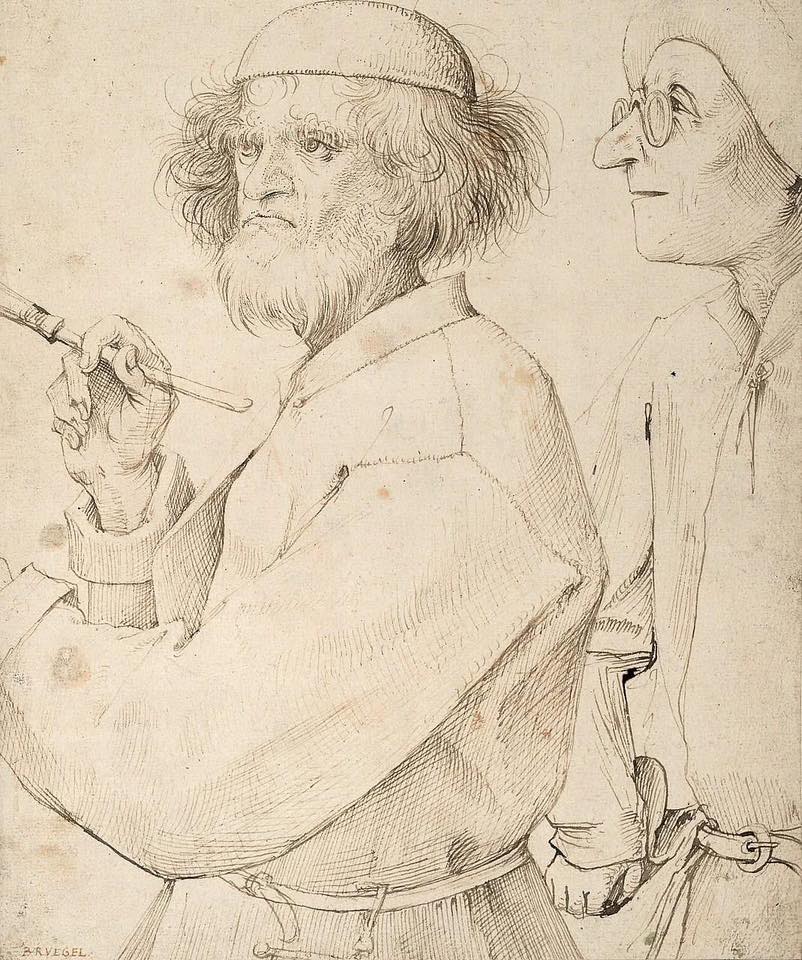

| Artist | Pieter Bruegel the Elder |

|---|---|

| Year | 1565 |

| Type | Pen and ink on brown paper |

| Dimensions | 25.5 cm × 25.1 cm (10.0 in × 9.9 in) |

| Location | Albertina, Vienna |

There’s something quietly unnerving about looking at a Bruegel painting. You start with a smile — the peasants dancing, stumbling, reveling — but the longer you look, the more the absurdity sets in. Then the cruelty. Then the echo of our own world reflected back through the centuries. Pieter Bruegel the Elder wasn’t merely a painter of village life. He was a kind of cultural x-ray machine — peering into the skeleton of society and laying it bare, with wit, empathy, and an almost surgical clarity.

Born around 1525, likely in or near Breda in the Netherlands, Bruegel was active during a time of deep religious and political upheaval. But he didn’t paint saints or kings. Instead, he filled his canvases with the masses — peasants dancing, harvesting, bickering, tumbling through life. From a modern lens, it’s easy to romanticize this focus, to cast Bruegel as some proto-ethnographer or champion of the everyman. That misses the point. He wasn’t documenting life — he was dissecting it.

A Drawing That Says Too Much: The Painter and The Buyer

Let’s begin with the image you’ll likely already have seen — The Painter and The Buyer, a drawing Bruegel made around 1565. It’s spare, almost quiet in its ink lines, yet it says volumes.

The artist sits, intent, stylus to board. Behind him looms a man in fine clothes, his mouth slightly agape, eyes bulging with curiosity — or condescension. It’s a scene that could be drawn today. The artist as craftsman, absorbed in his labor, while the patron hovers, eager to insert his own meaning, his own valuation. Bruegel is almost certainly portraying himself here — and not flatteringly. This is not self-celebration; it’s satire. It’s complaint.

The drawing works as both confession and critique — of the marketplace, of the transactional gaze. It’s also a masterclass in restraint. No lavish detail, no moralizing inscription — just two men caught in a moment of uncomfortable closeness. The viewer, like the buyer, is now implicated.

It’s the perfect introduction to Bruegel’s world: humorous, bitter, clear-eyed.

Rituals, Routines, and Relentless Motion

By the mid-16th century, Bruegel had trained under Pieter Coecke van Aelst and traveled through Italy — but you’d never confuse his work with that of the Italians. No idealized bodies, no perspective games, no marble flesh bathed in divine light. Bruegel gave us hunched backs, muddy fields, meals of bread and onions.

In The Peasant Wedding, the groom is almost invisible — a small figure to the left. What dominates instead is the table, the trenchers, the rhythm of labor. Everything feels slightly too real, too physical. These aren’t caricatures; they’re characters — participating in a social script older than any of them.

His landscapes, too, resist grandeur. Hunters in the Snow isn’t a celebration of nature — it’s a study in cold, fatigue, and the smallness of humans against the sweep of ice and sky. The dogs are lean. The hunters are bent with exhaustion. The village below offers little cheer. And yet it’s all beautiful — not in spite of the bleakness, but because of it.

There’s something about Bruegel’s perspective that feels almost godlike — detached, surveying, omniscient. He paints as though he sees everything at once: the central action, the peripheral absurdities, and the cosmic irony.

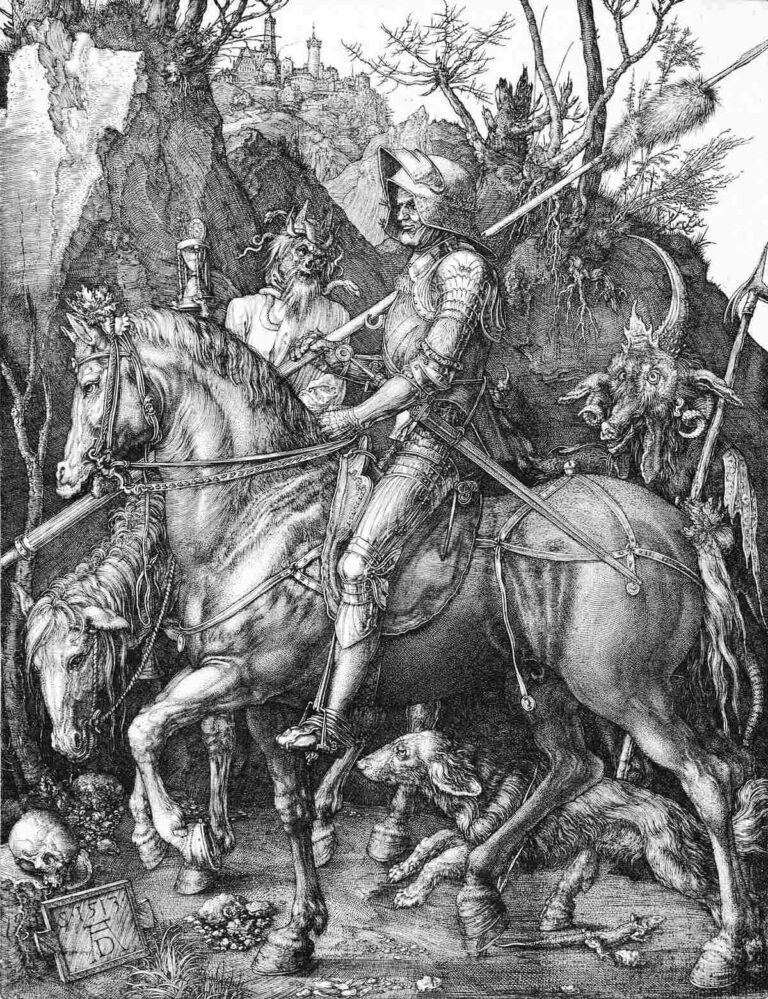

Of Idioms and Allegories: The Blind Leading the Blind

One of the most haunting works in Bruegel’s repertoire — and the subject of a thoughtful feature on Art Addict Galleria — is The Blind Leading the Blind (1568). This is not satire in the conventional sense. There’s no joke. Only despair, quietly rendered.

As detailed in the article, this painting walks a tightrope between literalism and allegory. A procession of blind men, linked by touch, stumbles forward in a diagonal tumble. The first has already fallen; the rest are doomed to follow. It’s not just a biblical proverb made visual — it’s a grim echo of human behavior.

What makes the scene so disturbing is how serene it is. The landscape is soft, pastoral, even tender. Yet it offers no help. The church steeple in the distance is dwarfed, a symbol drained of sanctuary. Bruegel shows the moment before the collapse, the hesitation before disaster, and makes us dwell there.

Napoli

The article rightly observes that this is one of Bruegel’s most “elegiac” works. It’s a lament, yes, but also a warning — about ignorance, about blind conviction, about following those who cannot see.

In a sense, The Blind Leading the Blind is the natural sequel to The Painter and The Buyer. One shows the artist at work, the other shows what happens when vision fails.

Folly, Famine, Fire: Bruegel’s View of the World

Bruegel was obsessed with human folly. Netherlandish Proverbs (1559) crams over 100 sayings into a single chaotic village scene — from “banging your head against a brick wall” to “having one foot in the grave.” It’s a feast of idiocy. But it’s also strangely sympathetic.

These aren’t villains. They’re just… us. Petty, confused, distracted. Bruegel doesn’t moralize — he observes. With surgical precision and a wry smile.

And when he isn’t smiling, he’s issuing some of the darkest visual sermons ever painted.

In The Triumph of Death, the sky is orange, the ground scorched, and skeletons swarm the earth, killing everyone in their path. There’s no escape — kings, lovers, peasants — all are dragged into the grave. It’s apocalyptic, but not fantastical. It feels earned. As if Bruegel were reminding his audience: this is what happens when we forget our place in the order of things.

It’s no coincidence that he made this work during the rise of the Spanish Inquisition and the early rumblings of the Eighty Years’ War. Bruegel wasn’t just looking backward to medieval death culture — he was staring directly at his own time.

The Last Works: Silence, Stillness, Surrender

In his final years, Bruegel’s works grew more sparse, more distilled. The Magpie on the Gallows (1568), painted just a year before his death, shows a gallows looming over a gentle landscape, with a bird perched atop it — watching. Below, peasants dance. Life, death, and indifference share a single frame.

There’s a chill to these last paintings. Not despair, exactly — but resignation. The world continues, indifferent to individual fate.

In one of the most haunting gestures of his life, Bruegel reportedly asked his wife to destroy some of his drawings after his death, fearing they might be politically dangerous. He knew too well how power works. And how images — even funny ones — can be used as evidence.

A Legacy Etched in Dust and Detail

What remains of Bruegel is extraordinary: about 40 paintings, over 60 drawings and engravings. And an influence that rippled through Rubens, Rembrandt, and even into modernity. His sons — Pieter the Younger and Jan the Elder — copied and adapted his work, ensuring that “Bruegelian” became a kind of visual language in itself.

But no one quite captured the bitter tenderness of the father. No one balanced mockery and mourning the way he did.

Bruegel is easy to admire but hard to categorize. He wasn’t a caricaturist, but he exaggerated. He wasn’t a preacher, but he moralized. He wasn’t a realist, but everything feels true.

He holds a mirror to us — cracked, yes, but uncomfortably accurate.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s art transcends time, offering viewers a lens into the past while prompting reflection on enduring human themes. His works, rich in detail and narrative, continue to captivate and inspire, solidifying his place as a master of the Dutch and Flemish Renaissance.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!