Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

Text by Vincent DeLuise Author, Educator, Musician at amusicalvision.blogspot.com, Cultural Ambassador, Waterbury Symphony Orchestra

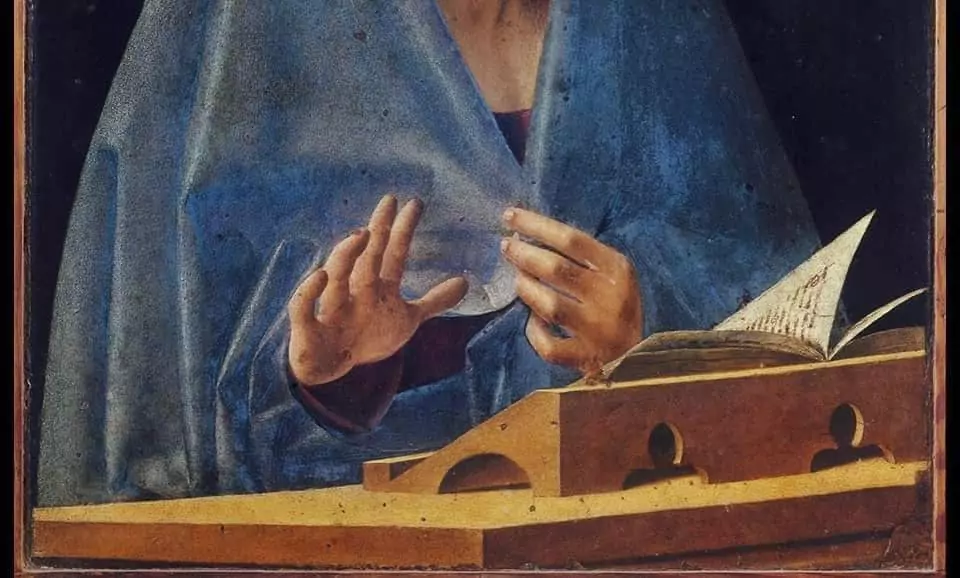

Artist : Antonello da Messina

Title : La Vergine Annunciata (The Virgin Annunciate)

Date : c.1476 , Dimensions : 47 cm x 33 cm (18 in. x 13 in.)

Medium : Oil on wooden panel

Collection : Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo, Sicily

“ Un colore nobile, bello, il più perfetto di tutti i colori”

Cennino Cennini, Il Libro dell’Arte, c.1400

(A noble color, beautiful, the most perfect of all colors)

There is Blue, with such evocative adjectival subspecies as navy, cerulean, baby, or powder. Then there is an unclassifiable Blue, a Blue that defies categorization and yet is decidedly Blue. The Blue to which I am referring is the breathtaking, ineffable Blue of the Palermo Madonna Annunciate, la Vergina Annunciata, of Antonello da Messina. The masterpiece I offer here is the Vergine Annunciata, the Virgin Annunciate, in Palermo at the Palazzo Abellis.

It is remarkable on a number of levels:

- The gaze of the Virgin, interrupted from her quiet reading by an invisible Angel of the Annunciation (the Archangel Gabriel, who would have been positioned exactly where we, the observers, are positioned);

- the foreshortening (Lo Scorcio) of the Virgin’s right hand as she is interrupted by the Angel of the Annunciation, the Archangel Gabriel;

What fabulous foreshortening!

Bellissimo Lo Scorcio !

Antonello’s splendid use of a dramatic scorcio (foreshortening) of the forearm behind the right hand of the Virgin amplifies the sense of volume, depth and three-dimensionality in his masterwork, thus augmenting reality in the illusion of a painted portrait.

- and that luminous light pervading the Virgin’s face and hand, bringing her dramatically out of the shadows.

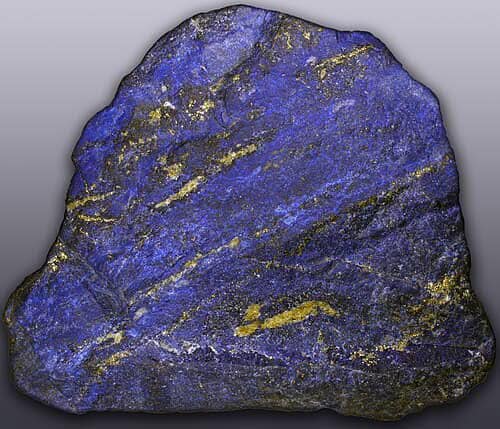

The Blue of Antonello was Ultramarine, the exquisite and rare Blue, alchemically transformed from ground Lapis Lazuli. Until the 1700s, the only source of Lapis was the remote Sar-e-Sang valley in the Badakhshan mountains in northeast Afghanistan, where it has been mined for six thousand years.

Cennino Cennini, the author of the early 15th century text, _Il Libro dell’Arte_ ( _The Book of Art_), describes the quasi-alchemical magic involved in taking Lapis Lazuli, grinding it down to a fine powder, and then, with some recondite legerdemain, transmuting it into ultramarine.

Ultramarine (literally, “beyond the sea,” which describes well the stone’s origin from the Sari-Seng mountains in Afghanistan through Persia and then across the Mediterranean Sea into the Adriatic to Venezia), is a conglomerate, a zeolite pigment containing azurite, pyrite and quartz.

Ultramarine is more stable than other blue pigments, most of which are other azurite derivatives which oxidize quickly to greenish-black.

Antonello da Messina (nato Antonello di Giovanni di Antonio, c. 1430 -1479) was one of those little known transformative geniuses. The legendary art historian John Pope-Hennessy described Antonello as “the first Italian painter for whom the individual portrait was an art form in its own right.”

- Antonello was born in Messina, on the eastern tip of Sicilia, trained in Napoli, and visited and worked a while in Venezia, but spent most of his time on that beautiful island at the toe of Italia.

- Antonello was one of the few southern Italian painters who influenced the style of northern italian artists.

- Antonello visited the Bellinis and their studio in Venezia in 1475.

- There is no documentation that he ever went north of the Alps.

If Antonello never went to Flanders, never went to Bruges or Antwerp or Louvain or Amsterdam, how did he come to possess a style that channeled Jan van Eyck and Petrus Christus?

How did Antonello figure out the merits of oil on panel to become one of the early adopters of this style in the Cisalpine regions?

Antonello likely learned the techniques of oil painting when he was a pupil of Niccolò Colantonio in Napoli around 1450. Colantonio (c. 1420 – 1460) learned the technique directly from the early Nederlandisch Hispano-Flemish masters who were invited to Napoli from Spain by the Aragonese ruler, King Alfonso V. During that period of training, Antonello also studied the works of the early Nederlandisch masters that were in the collection of Alfonso 1 of Napoli Alfonso V of Aragaon. Antonello may have also met one of Jan van Eyck’s greatest pupils, Petrus Christus, in Milano in 1456.

Antonello’s portraits are striking. Many of the dozen or so attested portraits show 3/4 views or full/frontal poses of his sitters, with dramatically dark tenebroso backgrounds, a chiaroscuro technique that Antonello employed a century and a half before Caravaggio. There are also in Antonello’s portraits identifying marks such as ledges, parapets, books or tabletops, that create volume and three-dimensionality and enhance the illusion of depth.

References:

1) Antonello da Messina, Metropolitan Museum monograph https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/…/p15324coll10/id/51392/

2) Kassia St Clair. The Secret Lives of Color https://www.amazon.com/Secret-Lives-Color…/dp/0143131141

3) Symbols as colors in Rinascimento Art, https://artgreet.com/symbols-in-renaissance-art/

4) Marcia Hall. Color and Meaning: Practice and Theory in Renaissance Painting. Cambridge University Press 1992

Text by Vincent DeLuise Author, Educator, Musician at amusicalvision.blogspot.com, Cultural Ambassador, Waterbury Symphony Orchestra

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!