Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

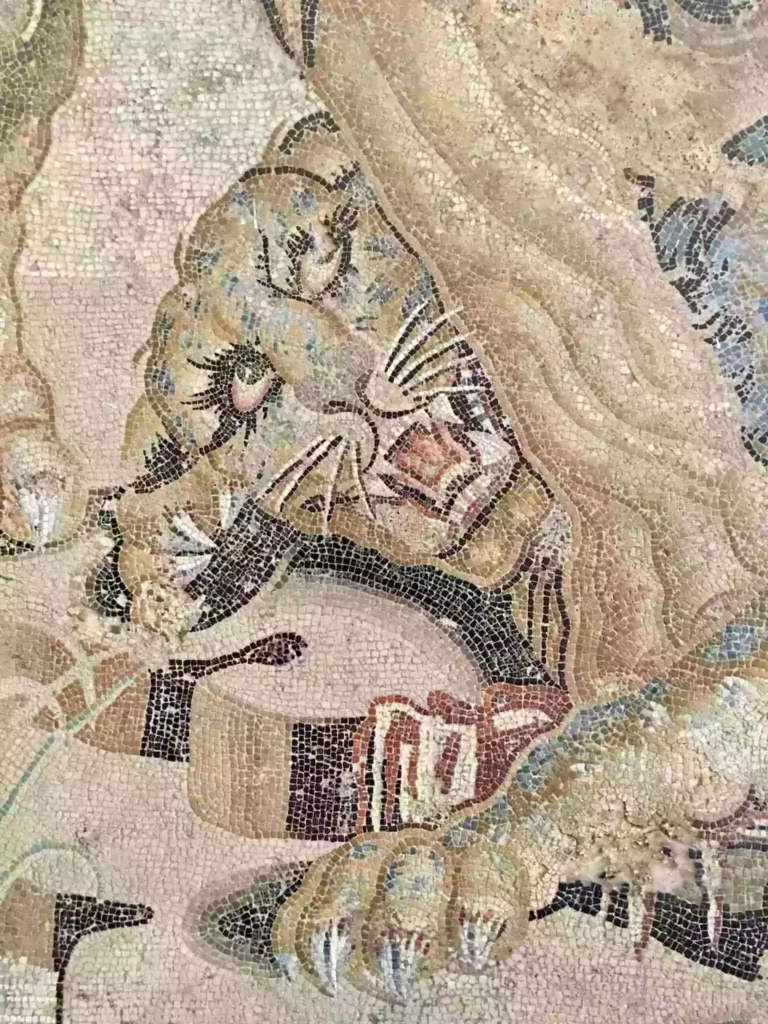

| Title | Mosaic of a lion that clutches a leopard among marshy leaves. |

| Origin | Pompeii. Casa delle Colombe or House of the Mosaic Doves |

| Date | 1st century BC – 1st century AD |

| Medium | mosaic |

| Current Location | Naples Archaeological Museum, inv. no. 114282. |

The lion’s mouth is wet with blood. Its claws sink into the struggling panther beneath. The panther’s eyes remain wide open, fixed and glassy, as if caught at the threshold between life and myth. We do not witness a hunt; we are pulled into a moment of symbolic arrest, into a performance between predator and prey captured in tesserae and ochre on the floor of a Roman villa. This is not merely a mosaic. It is a confrontation, a mirroring, a stage where wild nature and Roman civilization eye each other with suspicion, fascination, and defiance.

The mosaic in question, a fragment once gracing the opulent floors of the Casa delle Colombe (The House of the Doves) in Pompeii and now preserved in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, is a masterpiece of the Roman illusionistic tradition. And yet it offers more than aesthetic flourish. Behind its stylized tendrils of mane and bleeding snout lies an entire worldview—a system of signs in which animals are not animals but masks, not ornaments but oracles. This article proposes that this lion and its doomed adversary serve as mirrors of Roman identity, conduits of myth, and emblems of power, emotion, and the tenuous line between civility and savagery.

I. Mosaic as Medium: Laying Down Empire in Stone

Before we step into interpretation, we must understand the medium. Roman mosaic, especially of the late Republican and early Imperial periods, was more than decorative flooring. It was imperial philosophy underfoot. Every tessera, carefully placed by craftsmen trained in the Hellenistic tradition, was a calculated pixel in an image meant to endure time, wine spills, footsteps, and the scorn of future ages.

In elite Roman houses—the domus—mosaics were not neutral backgrounds. They were programmatic. Just as frescoes narrated mythic scenes on walls, mosaics on floors were part of a choreographed spatial experience. One walked across heroes, gods, wild animals, and epic battles; one was reminded constantly of what it meant to be Roman: master of nature, heir to Greece, participant in myth. The Casa del Fauno itself—among the largest private homes in Pompeii—contains the famous Alexander Mosaic, a dramatic tableau of Alexander the Great in combat with Darius. It is therefore no accident that the same house housed this violent animal scene. Here too is a drama of conquest, only more primal.

II. Animal as Allegory: The Panther and the Lion

The lion has long served as an emblem of royalty and conquest in ancient cultures, from the leonine guardians of Assyrian palaces to the hunting scenes in Achaemenid bas-reliefs. The Romans, inheriting both Hellenistic and Near Eastern iconographies, reinterpreted these animals within their own framework of domination. In Roman visual language, lions are not only real predators—they are metaphors. A lion may be Hercules, may be Rome itself, may be the raw power of nature harnessed into an emblem of strength and courage.

But what of the panther? Its identity is more elusive. In Roman art, panthers are often linked to Dionysus—the god of wine, ecstasy, and ritual madness. Dionysian processions frequently include panthers and leopards, their spotted pelts shimmering as they pull the god’s chariot. They symbolize more than exoticism; they are the avatars of instinct, of wildness tamed only temporarily by the seductive, intoxicating power of divine pleasure.

To place a lion and a panther in mortal combat is, then, to stage a ritual of Roman ideology: virile order (lion) overcoming ecstatic chaos (panther), martial domination overpowering the libidinal and the foreign. This is not just a scene of nature red in tooth and claw—it is a mythic reenactment of Roman values defeating the Other.

III. Eyes That Speak: The Gaze of the Animal Mask

And yet, for all this ideological comfort, there is something unsettling in the panther’s eye. The eye is painted with uncanny precision, glossy and rounded, with a depth that transcends decorative convention. It is not a scream, not a plea—but a gaze.

This gaze interrupts the triumphalist reading of the scene. Suddenly, we are implicated. The viewer, formerly confident in Roman supremacy, must reckon with the humanity—yes, the humanity—of the animal. This is the power of what we might call the “animal mask” in Roman art: it is not about realism, nor about anthropomorphism, but about confrontation. The animal, rendered with such eerie emotion, becomes a threshold creature, a mask that both hides and reveals. It offers no fixed interpretation, only a suspended tension between beast and god, between victor and victim, between seen and seer.

In this, Roman mosaic participates in a broader Mediterranean tradition of sacred bestiaries. Just as Egyptian deities wore animal heads to express divine functions, Roman mosaics use animal visages to articulate human passions: anger, lust, courage, madness. In these eyes lives a dramaturgy of power.

IV. The Performance of Virtus: Masculinity, Control, and Violence

Let us descend from the spiritual to the social. Why would a Roman patron choose such a ferocious image for his floor? The answer lies in virtus—the Roman ideal of masculine strength, courage, and self-discipline. Roman elite masculinity was performative. It was not enough to possess power; one had to display it.

In this context, the lion’s domination over the panther is an allegory of control: of self over impulse, of Roman over barbarian, of man over woman (the panther is often coded as feminine in ancient bestiaries). The scene flatters the viewer by inviting identification with the predator, not the prey. The blood is part of the spectacle. It is a visual theater of imperium—rule enacted through violence, but aestheticized.

That the scene appears in a domestic context is no contradiction. Roman homes were not private in the modern sense; they were semi-public arenas where power was staged. To host a dinner over such a mosaic was to invite guests into a cult of domination, a shared belief in civilization’s right to impose its vision on the wild.

V. The Dionysian Shadow – Ecstasy and Horror in the Roman Imagination

And yet, again, there is ambiguity. The panther, associate of Dionysus, was not a mere symbol of foreignness. Dionysus himself was revered across the empire. His cult, with its processions and mask-wearing rituals, was deeply ambivalent—celebrating both joy and dissolution, ecstasy and madness. In this light, the death of the panther is not merely an act of conquest but a suppression of alterity—of the irrational, the ecstatic, the feminine, the Eastern.

The scene’s horror lies in its beauty. The blood is stylized, the death theatrical. It is artfully orchestrated like a Dionysian tragedy. In fact, the entire mosaic can be read as a kind of anti-Bacchic rite: instead of intoxication, order; instead of release, control. But this order is haunted by what it suppresses. Like the Roman amphitheater itself, where real animals were killed for spectacle, the mosaic aestheticizes death while denying the viewer clean moral footing.

VI. Animal Masks Beyond Pompeii – A Mediterranean Bestiary

This image is not unique. Across the Roman world, from Antioch to North Africa, mosaics depicting animal combat proliferated. Lions fight bulls, panthers stalk deer, griffins claw at antelopes. These scenes form a genre—the venatio—linked both to hunting and the games of the arena. But they also reveal something deeper: a collective Roman obsession with the boundary between nature and culture.

The animal mask becomes a canvas on which Rome projects its anxieties and ambitions. In Africa Proconsularis, mosaics often featured exotic beasts never seen in Italy—elephants, giraffes, crocodiles. Their presence symbolized Rome’s global reach. But the more these beasts appear, the more their symbolic meanings shift. They become less naturalistic and more iconic, participating in a visual lexicon where every spotted pelt and snarling mouth means something beyond itself.

In this visual ecosystem, predators are not just beasts—they are signifiers. Their ferocity becomes an allegory of power. Their gaze, when returned, becomes a moment of rupture.

VII. From Mosaic to Mirror – Who Hunts Whom?

Ultimately, the genius of the Casa delle Colombe mosaic lies in its double address. On one level, it celebrates domination—Rome over nature, man over beast. On another, it destabilizes that confidence. The gaze of the dying animal transforms the mosaic from a narrative into a mirror. Who is the hunter, and who the hunted?

This ambiguity is not a failure of propaganda but its refinement. The Roman elite could afford complexity. The same man who worshiped Bacchus might also commission his death in stone. The same floor that celebrated bloodshed might also suggest, subtly, its cost.

Therein lies the power of Roman art—not in its consistency, but in its contradictions. The animal mask is both a symbol and a question. It asks us to confront the nature of power—not as an abstract virtue but as an embodied, violent, unstable force. And in that confrontation, we see not only the Roman worldview but our own.

Epilogue – The Gaze That Persists

The panther’s eye, frozen in time, has survived the volcano, the Empire, and the centuries of dust. It still looks. Not at a Roman patrician anymore, but at us. It dares us to look back. To ask what it meant—and still means—to kill beauty for the sake of control, to aestheticize violence and call it culture.

In this mosaic, art becomes ritual, and the ritual remains unfinished. The floor does not merely depict a hunt—it performs one. And the viewer, invited to walk across it, becomes part of the spectacle.

So tread carefully. The hunter is watching. And so is the prey.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!