Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

The Italian Renaissance wasn’t just a chapter in history—it was a rebirth, an explosion of creativity that reshaped the world forever. Emerging from the shadows of the Middle Ages, Italy in the 14th to 17th centuries became a powerhouse of intellect, artistry, and innovation. It was a time when the past met the future, when ancient wisdom blended with fresh perspectives, birthing a golden age that still captivates us today.

The Spark That Ignited a Cultural Fire

What caused this awakening? Many factors played a role. Italy’s city-states—Florence, Venice, Rome—were economic hubs, buzzing with trade and wealth. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 brought a flood of scholars carrying ancient Greek and Roman texts, fueling a hunger for classical knowledge. The Medici family, rulers of Florence, poured their wealth into supporting artists, philosophers, and architects, creating an environment where creativity flourished. And let’s not forget the humanists—intellectuals who believed in the power of human potential, shifting the focus from divine authority to individual achievement.

Key factors contributed to the rise of this extraordinary movement:

- The Revival of Classical Knowledge: Scholars rediscovered ancient Greek and Roman texts, inspiring a return to classical ideals in art, architecture, and philosophy.

- Economic Prosperity: The wealth accumulated through trade and banking allowed patrons like the Medici family to support artists, architects, and scholars.

- Political Competition: Rivalries between city-states such as Florence, Venice, and Milan fueled advancements in art and culture as rulers sought to showcase their power and prestige.

- The Fall of Constantinople (1453): The Ottoman conquest led to an influx of Greek scholars into Italy, bringing with them invaluable classical manuscripts.

- The Printing Press (1440s): The invention of movable type by Johannes Gutenberg facilitated the widespread dissemination of Renaissance ideas across Europe.

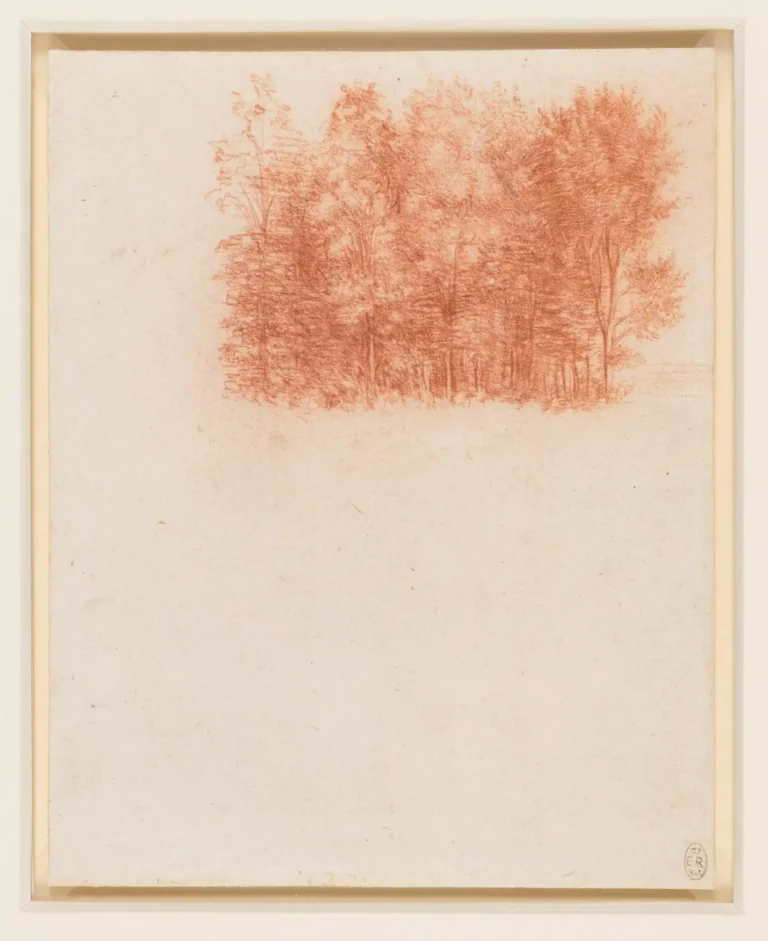

Art That Defined an Era

Art wasn’t just decorative during the Renaissance; it was revolutionary. Perspective, light, and realism took center stage. Giotto paved the way with his emotive frescoes, but it was Masaccio who truly grasped depth and anatomy. And then came the titans: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael.

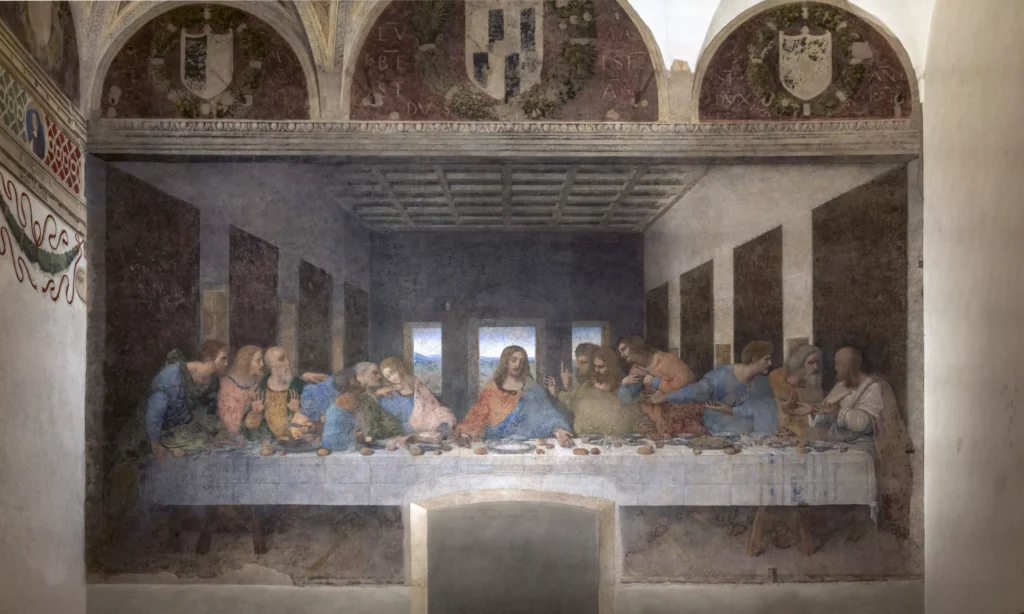

Leonardo, the ultimate polymath, painted the enigmatic Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, but he was equally obsessed with anatomy, flight, and engineering. Michelangelo sculpted the breathtaking David and painted the Sistine Chapel ceiling—a feat of divine and human ambition intertwined. Raphael brought grace and harmony to his works, his School of Athens celebrating the great thinkers of antiquity with stunning realism.

But art wasn’t confined to painting and sculpture. Architecture saw the revival of classical forms, with Filippo Brunelleschi mastering linear perspective and designing the awe-inspiring dome of Florence Cathedral.

Key Artists and Their Masterpieces

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

Often regarded as the quintessential Renaissance man, Leonardo da Vinci was not only a master painter but also an engineer, scientist, and inventor. His most famous works include:

- Mona Lisa (1503–1506): Renowned for her enigmatic smile and the masterful use of sfumato (a technique for soft transitions between colors).

- The Last Supper (1495–1498): A dramatic portrayal of Jesus and his disciples, showcasing Leonardo’s pioneering use of perspective and composition.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564)

Michelangelo’s unparalleled skill in sculpture, painting, and architecture made him one of the most celebrated figures of the Renaissance. His most iconic works include:

- David (1501–1504): A stunning marble statue symbolizing strength and ideal beauty.

- The Sistine Chapel Ceiling (1508–1512): A breathtaking fresco depicting scenes from Genesis, including the famous Creation of Adam.

- The Last Judgment (1536–1541): A grand fresco covering the Sistine Chapel’s altar wall, illustrating Michelangelo’s dramatic and expressive style.

Raphael (1483–1520)

Known for his grace and harmony, Raphael’s works epitomize the Renaissance ideal. His major contributions include:

- The School of Athens (1509–1511): A fresco celebrating classical philosophy, featuring figures such as Plato, Aristotle, and a self-portrait of Raphael himself.

- Sistine Madonna (1512): A masterpiece known for its ethereal beauty and the famous cherubs at the bottom.

Titian (1488–1576)

A master of Venetian painting, Titian was known for his rich colors and dynamic compositions. His works include:

- Assumption of the Virgin (1516–1518): A vibrant depiction of the Virgin Mary ascending to heaven.

- Venus of Urbino (1538): A sensual yet sophisticated portrayal of the goddess Venus.

Literature, Science, and the Human Mind

While artists were reshaping visual culture, writers were redefining thought. Dante’s Divine Comedy bridged the medieval and modern worlds. Petrarch, the “father of humanism,” revived interest in Roman texts, and Boccaccio’s Decameron captured the spirit of a society in transition. Later, Machiavelli’s The Prince laid the foundation for political realism, a book that still resonates today.

Science and exploration were equally transformed. The Renaissance mindset encouraged curiosity, leading figures like Galileo Galilei to challenge old ideas. His support for heliocentrism (the idea that the Earth orbits the Sun) shook the foundations of established doctrine. Meanwhile, explorers like Christopher Columbus and Amerigo Vespucci, armed with improved navigation techniques, ventured into unknown worlds, forever altering global history.

Key Figures in Renaissance Science

- Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543): Proposed the heliocentric model of the solar system, challenging the long-held belief that Earth was the center of the universe.

- Galileo Galilei (1564–1642): Improved the telescope, made groundbreaking astronomical observations, and supported Copernican theory.

- Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564): Published De humani corporis fabrica, a detailed study of human anatomy that revolutionized medical knowledge.

- Leonardo da Vinci: His notebooks contain sketches of flying machines, anatomical studies, and mechanical inventions far ahead of his time.

Notable Humanists

- Petrarch (1304–1374): Known as the “Father of Humanism,” he revived interest in Roman literature and philosophy.

- Erasmus (1466–1536): A Dutch scholar who promoted critical thinking and religious reform.

- Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527): Author of The Prince, a political treatise on power and strategy.

The Spread and Evolution of the Renaissance

Though it began in Italy, the Renaissance was too powerful to stay contained. As trade, travel, and the printing press spread ideas across Europe, France, Germany, and England saw their own cultural revivals. The Northern Renaissance, while inspired by Italy, took on its own identity—Albrecht Dürer’s engravings, Jan van Eyck’s precise oil paintings, and the literary genius of William Shakespeare defined this broader movement.

By the 17th century, the Renaissance began evolving into the Baroque period, with its grandeur and drama. But its core ideas—humanism, artistic mastery, scientific exploration—never faded. We still feel its influence today in everything from art and architecture to philosophy and politics.

Renaissance influence can be seen in:

- The Baroque Period: The artistic innovations of the Renaissance paved the way for the dramatic and expressive style of the Baroque era.

- The Enlightenment: The emphasis on reason, observation, and individualism influenced 18th-century thinkers.

- Modern Science and Exploration: The scientific breakthroughs of the Renaissance laid the foundation for modern physics, astronomy, and medicine.

- Democratic Ideals: Renaissance humanism contributed to later political movements advocating for individual rights and democracy.

The Renaissance wasn’t just a historical period; it was a mindset—a belief in progress, discovery, and the boundless potential of human creativity. We still stand in awe of Michelangelo’s frescoes, lose ourselves in Da Vinci’s notebooks, and admire the intellectual daring of thinkers like Galileo and Machiavelli.

More than a rebirth, the Renaissance was a revolution. And like all great revolutions, its echoes never truly fade.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!