Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

| Artist | Diego Velázquez |

|---|---|

| Title | Rokeby Venus |

| Year | c. 1647–1651 |

| Medium | oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 122 cm × 177 cm (48 in × 70 in) |

| Location | National Gallery, London. |

You don’t forget the first time you see her. Reclined, bare, her back turned to you yet completely aware of your presence, the Rokeby Venus is less an object of desire than a quiet confrontation. She doesn’t seduce you; she studies you. She makes you the subject. And for centuries, that has unsettled more than a few people.

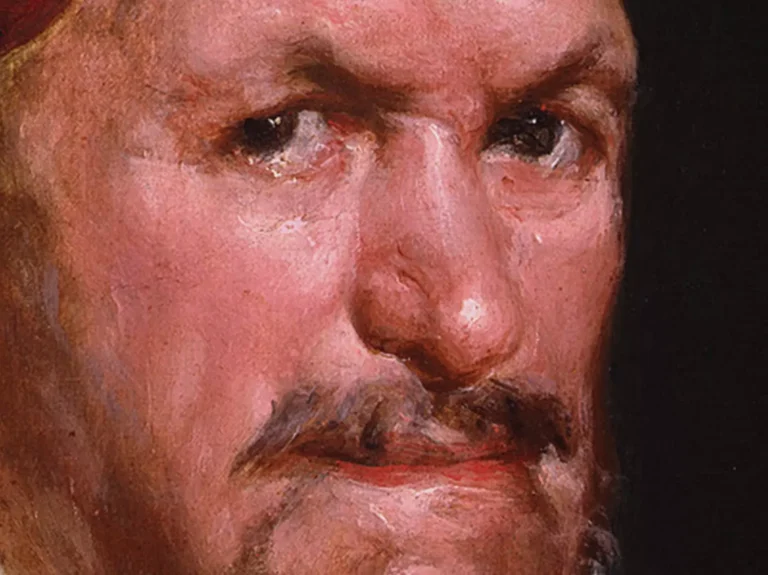

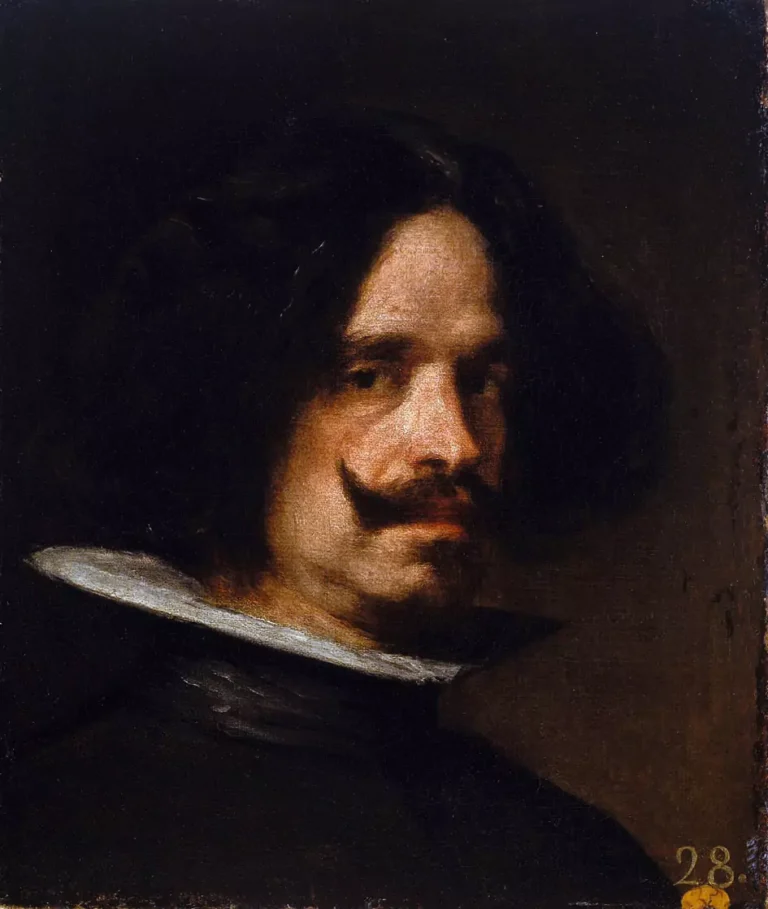

Painted around 1647–1651 by Diego Velázquez, this is his only surviving nude. The Spanish court painter famous for papal portraits and royal infantes didn’t usually venture into sensual territory. Spain at the time wasn’t exactly France. Nudity was suspicious, not admired. It flirted with the heretical. And yet here it is: this startling, delicate image of Venus seen from behind, her face reflected in a mirror held by a winged Cupid.

But what makes this painting truly compelling is not just what you see, but what happened to it after the paint dried. It is a work stalked by strange luck, bad owners, shipwrecked fortunes, and a political stabbing that turned it from a museum piece into a weapon.

Whispers of a Curse

We don’t know who originally commissioned the Rokeby Venus, but the first documented owner—a Madrid merchant—reportedly suffered a series of spectacular misfortunes after buying the painting. His overseas cargo vanished into the sea. Piracy? Weather? It hardly mattered. His fortune collapsed, and he sold the Venus to another merchant. The second owner’s warehouses were struck by lightning and burned to the ground.

The painting passed to a wealthy moneylender, who had it just long enough for someone to rob and stab him in a Madrid alley. Coincidence? Of course. But Spain in the 17th century had a talent for assigning meaning to misfortune, and soon the painting picked up a reputation. Bad luck follows her, they said.

Boudoir Provenance

The curse didn’t deter powerful collectors. By the late 18th century, the Venus had found a more romantic setting: the private rooms of the Duchess of Alba, famously painted nude and clothed by Goya. The Rokeby Venus hung in her boudoir beside Goya’s “Maja Desnuda,” turning the space into a whispered scandal.

Later, the painting entered the collection of Manuel Godoy, Spain’s Prime Minister and the queen’s rumored lover. Godoy was no stranger to erotic art, and his taste in paintings mirrored his political downfall: grand, decadent, and eventually doomed. After Napoleon’s invasion, his collection was scattered.

From there, the Venus made her way to England, renamed after Rokeby Park, where she quietly joined the ranks of continental masterpieces collected by the British aristocracy. She might have faded into stately home obscurity if not for the National Gallery’s acquisition in 1906.

And then came the knife.

The Woman Who Stabbed Venus

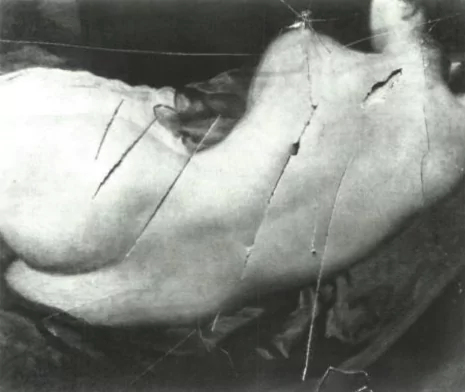

March 10, 1914. Suffragette Mary Richardson walked into the National Gallery with a meat cleaver hidden under her coat. She approached the painting, waited until the guard turned, and then slashed it across the back. Not once. Several times. The canvas tore open like skin. The press, scandalized, dubbed her the woman who mutilated Venus.

Richardson later explained herself: she was protesting the arrest of Emmeline Pankhurst, the suffragette leader. And she chose the Venus precisely because people, she said, “would do nothing against the destruction of a woman’s body as long as it was painted.”

That sentence lingers. It forces us to ask: what does it mean to admire beauty that cannot speak for itself? What is the line between worship and ownership? Between art and objectification?

The irony is that Richardson didn’t destroy the painting. It was restored, carefully, and today you’d have to squint to find the scars. But that act shifted the Venus’s story. She wasn’t just a reclining nude anymore. She was a battlefield.

A Mirror That Stares Back

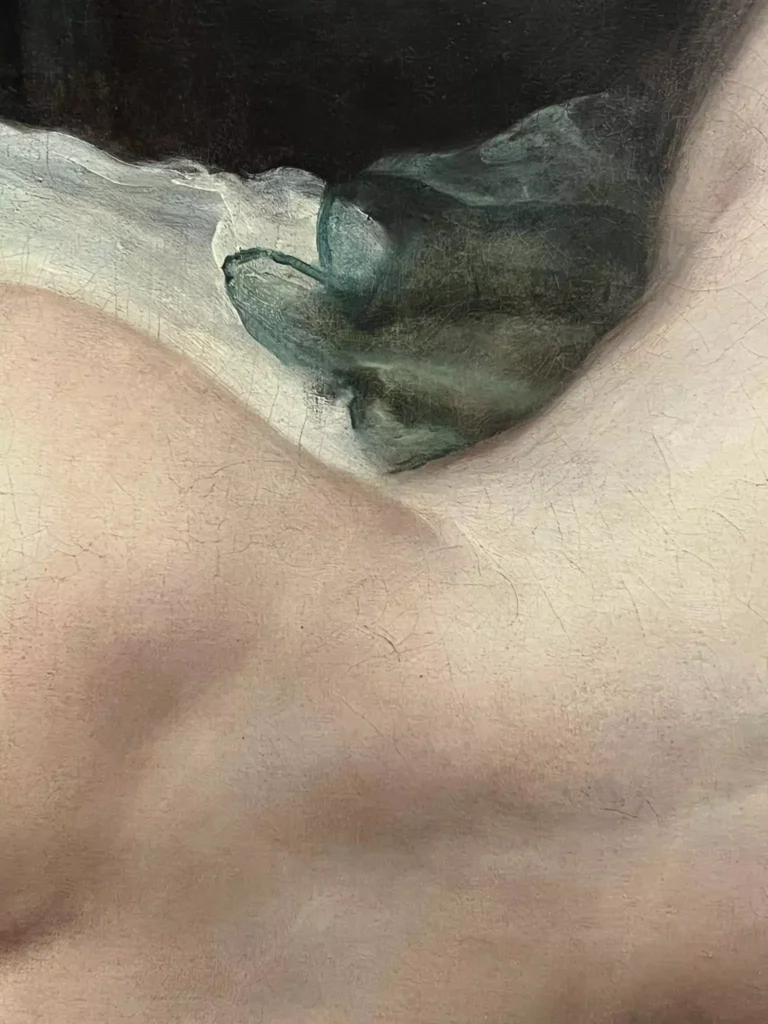

Velázquez was too clever to paint a traditional Venus. Instead of displaying her beauty front-on, he places her with her back to us, her face only visible in the mirror. And what a face it is: softly blurred, enigmatic, maybe even impossible. Is it the reflection we’d expect? Is she really looking at herself? Or us?

Some scholars argue the mirror isn’t a mirror at all, but a deliberate trick. The angle is wrong. The proportions are off. We aren’t seeing her reflection; we’re being watched. That tiny shift changes everything. She’s not passive. She’s aware. She catches us looking and holds the gaze.

And perhaps that, more than any whisper of eroticism, is what made people nervous.

Velázquez, the Realist in Disguise

Diego Velázquez was no radical. He was a court painter, a diplomat, a man who knew how to navigate politics. But in his best works—”Las Meninas,” especially—he plays a quiet game of subversion. He uses perspective, reflection, and space to twist expectations.

The Rokeby Venus fits that pattern. Yes, it borrows from Titian and Rubens, artists who loved painting Venus with glowing skin and flowing hair. But Velázquez makes it cooler. The body is real, soft but unidealized. There’s a restraint here that hints at something deeper than pleasure.

It’s also intimate. There’s no golden apple, no divine entourage, no doves. Just a woman, her child-like Cupid, and a mirror. It could be any room. And maybe that’s what still catches us off-guard. She’s not mythic. She’s human.

The Afterlife of a Painting

The Rokeby Venus has survived theft, fire, politics, and a cleaver. Today, she hangs quietly in the National Gallery, behind a protective screen, though few visitors know why.

If you stand before her long enough, you’ll notice something strange. The mirror shifts, depending on where you stand. Her gaze never quite settles. And as museum crowds move and scatter, as phones rise and snap her reflection, she remains still.

But make no mistake: she is watching.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!