Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

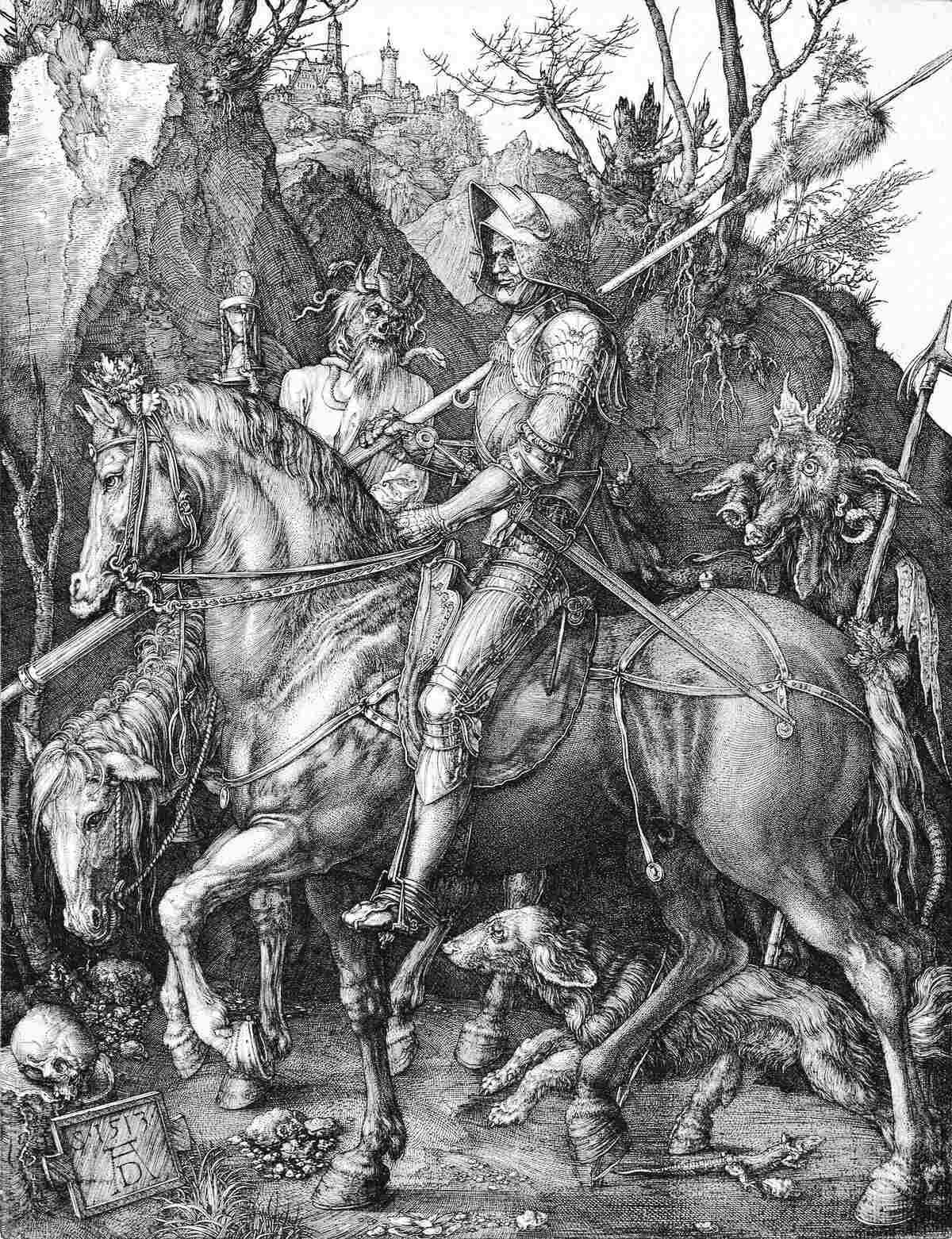

You stand before it, drawn into its dense forest of cross-hatched shadows and shimmering lines. There’s a knight, straight-backed and calm, riding his muscular steed with firm dignity. He is armored from head to toe, his visor half-lifted to reveal a stoic, focused face. Around him, things twist and slither: a skeletal figure holding an hourglass, a horned beast leering from the darkness, a landscape where life and decay coexist. This is Albrecht Dürer’s Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513), one of the most mythically charged and philosophically dense images of the Northern Renaissance.

To truly understand this engraving, you need to set aside your modern sensibilities. This isn’t just about medieval chivalry. It’s about dread. It’s about the unshakable tension between life’s call to virtue and the ever-present whisper of mortality. And it’s about what it means to keep moving forward, even as Death dogs your heels and the Devil grins just over your shoulder.

The Birth of a Moral Image

Dürer created this work in 1513, during a period when he was also producing Melencolia I and Saint Jerome in His Study. These three prints are often grouped together as his “Meisterstiche” or master engravings. But of the trio, Knight, Death, and the Devil feels the most narrative. It pulls you into a journey.

You follow the knight into the woods, almost physically. You feel the slow march of time. The sense of purpose in his posture is contagious. For many critics—from Erwin Panofsky to more recent voices like Jonathan Jones—this engraving represents the ideal of the Christian knight: a figure inspired by Erasmus, pressing forward with unwavering moral resolve.

But what are we to make of the creatures surrounding him?

Death Rides Close

Death is depicted not as a distant abstraction but as an intimate, almost mundane presence. He is no grim wraith with a scythe. Instead, Death is gaunt and ragged, holding an hourglass, his eyes sunken yet calm. He doesn’t threaten; he reminds. He offers time as both limit and gift.

You might find your gaze shifting uncomfortably to the hourglass. It’s tilted, mid-shake. Sand is falling. You don’t know how much is left. That’s the genius of Dürer: he doesn’t shout. He whispers. And it’s that quiet ticking you hear beneath the hooves.

The Devil Behind Us

On the knight’s other side lurks the Devil. Dürer’s Devil is grotesque: part goat, part lizard, with curling horns and a wild expression. He is a manifestation of temptation, chaos, confusion. And yet—here’s the striking part—the knight does not look at him. Nor at Death.

The knight looks straight ahead.

This has fascinated art historians for centuries. Panofsky believed this shows stoic resolve, the triumph of human will guided by divine virtue. The knight is on the narrow path, as suggested by Psalm 23: “Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.”

Dürer’s Line – Precision and Philosophy

The engraving is breathtaking in its detail. Every strand of the horse’s mane, every vein on the knight’s gauntlet, every thorn and twig along the trail is etched with relentless precision. This is not just technical brilliance; it’s psychological. Dürer uses line not to decorate, but to trap the eye, to tangle you in the world of the image.

You are forced to stay in the picture.

Even the background—a castle on a distant cliff, bare trees clawing at the sky, a loyal dog at the knight’s side—speaks to allegory. The dog, likely a symbol of loyalty or faith, presses close. He is the companion that never questions. He knows the way.

A Mirror of Inner Conflict

What makes Knight, Death, and the Devil so enduring is that it is not merely a religious or moral parable. It is psychological. It recognizes that life is a corridor lined with fear, but that one can walk it with grace. It reminds you that dread and virtue often walk side by side.

In a way, the image doesn’t answer questions. It raises them. Can you remain steadfast when fear closes in? Are you marching toward an ideal, or are you simply trying to stay ahead of death? Is the Devil behind you because you’ve outrun him—or because he knows you too well?

Renaissance and Modern Eyes

To Dürer’s contemporaries, the work may have read like a visual sermon. But to you, the modern viewer, it speaks of anxiety and agency. Dürer anticipated what Kierkegaard and Camus would later write about: the confrontation with the absurd, the necessity of meaning in the face of nihilism.

Jonathan Jones once described this engraving as “one of the most unnerving images ever made.” And yet, it is also strangely comforting. It doesn’t deny death. It doesn’t sugarcoat evil. It simply asks: can you keep going?

And in that question lies its power.

Beyond Allegory – The Personal Dürer

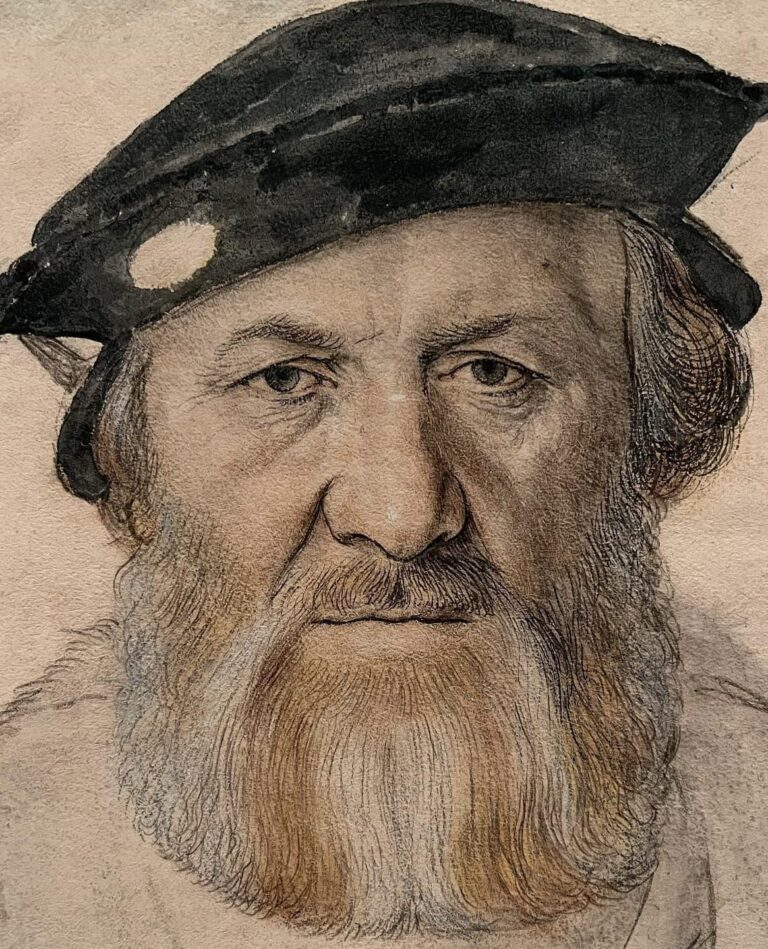

Some critics have noted that Dürer’s fascination with death may have stemmed from his own life anxieties. He created this piece shortly after losing his mother, and in the midst of political instability and rising Protestant movements. Was the knight a projection of Dürer himself? Was this an image to steel his own resolve?

There’s evidence to support this. In his letters, Dürer often expressed feelings of dread and spiritual unrest. His self-portraits show a man deeply concerned with his role in the world. The knight might not be a crusader. He might just be a man trying to stay upright.

So Why You Still Stare?

More than 500 years later, you still look at Knight, Death, and the Devil and feel that slow unease crawl up your spine. Not because it shocks, but because it understands. Dürer etched into copper what you still feel on sleepless nights: that to live is to press forward through shadows.

This engraving is not merely a historical artifact. It is a compass. Not a tool of direction, but of resilience. You don’t need to be a knight. You just need to ride forward.

Even if Death follows. Even if the Devil smiles. Even if you’re afraid.

You go on.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!