Looking for a muse? Check no further. Discover the Best of Art, Culture, History & Beyond!

Wassily Kandinsky, Joyous Ascent (Fröhlicher Aufstieg), 1923

- Artist: Wassily Kandinsky

- Title: Joyous Ascent (Fröhlicher Aufstieg)

- Year: 1923

- Medium: Lithograph

- Dimensions: Varies (as part of the Meistermappe des Staatlichen Bauhauses)

- Edition: Part of the Masters’ Portfolio (Meistermappe) of the Staatliches Bauhaus

- Style: Geometric abstraction, Bauhaus

- Technique: Lithographic printing

A Composition in Pure Energy

Some paintings don’t just sit still on the page—they pulse, vibrate, and hum with an inner dynamism that seems to lift them right off the surface. Kandinsky’s Joyous Ascent (Fröhlicher Aufstieg), a lithograph from his Masters’ Portfolio of the Staatliches Bauhaus (1923), is exactly that kind of work. It’s not simply an arrangement of colors and forms; it’s a composition that climbs, a visual music score where each note rises higher. And for Kandinsky, art was always about more than the eye—it was about the soul.

By 1923, Kandinsky was deeply embedded in the Bauhaus movement, refining a language of abstraction that sought to unify art, music, and spirituality. His works from this period—geometric, bold, and deeply considered—are far from his earlier, more expressive pieces. But that doesn’t mean they lack emotion. On the contrary, Joyous Ascent is filled with an electric optimism, an upward motion that mirrors its title. The work is a masterclass in Kandinsky’s theories of color, form, and composition, all working in harmony to create an image that resonates on an almost subconscious level.

The Bauhaus Connection: Structure, Color, and Philosophy

The early 1920s saw Kandinsky refining his artistic vision within the Bauhaus school, where he taught alongside artists like Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, and Josef Albers. The Bauhaus philosophy aimed to unify fine arts with applied arts, to bring clarity, order, and a sense of design into every aspect of life. This new approach aligned perfectly with Kandinsky’s belief in the spiritual power of form and color.

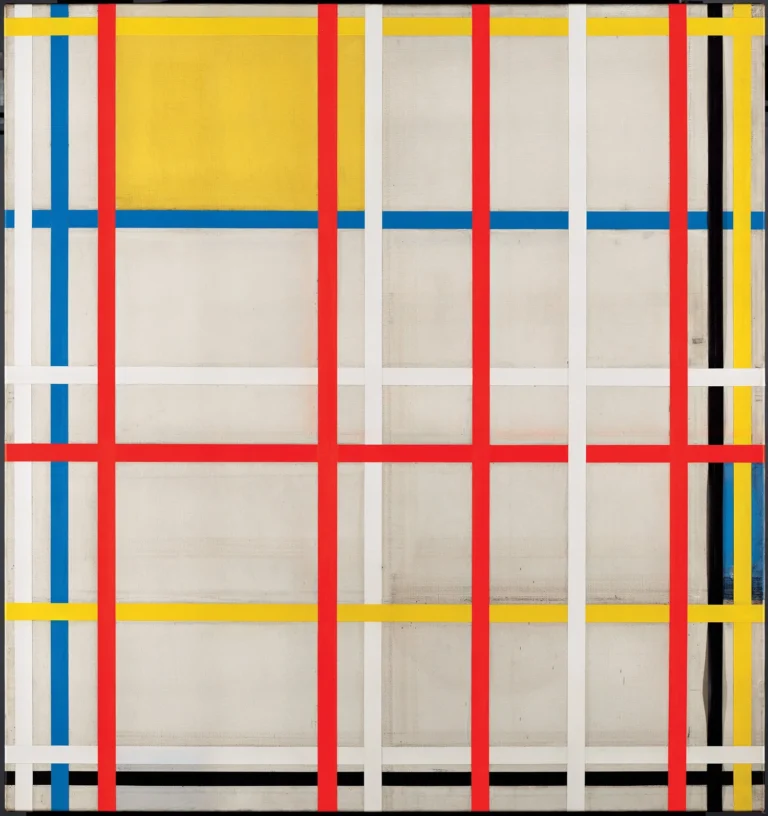

In Joyous Ascent, we see the Bauhaus influence in full force. The composition is structured yet dynamic, built from an array of geometric forms—triangles, circles, and arcs—that seem to shift and climb like a jazz improvisation. Each shape plays its role in a larger symphony of movement, a theme Kandinsky often likened to music. For him, a yellow triangle or a blue circle was not just a shape; it was a note in a universal, non-verbal language of emotional resonance.

Breaking Down the Composition

At first glance, Joyous Ascent may seem purely abstract, but Kandinsky’s meticulous sense of structure suggests otherwise. Every line and shape is positioned with intent, guiding the viewer’s eye along an invisible path. The upward trajectory is undeniable—like steps of a staircase leading toward some unseen summit. But what makes this work so thrilling is the interplay between balance and tension. There’s a sense of control, yet within that, an unpredictable liveliness, as if the forms are in constant negotiation with one another.

- Color & Energy: The sharp, angular forms in this work contrast beautifully with the rich palette of reds, yellows, blues, and blacks. These are not colors chosen at random—Kandinsky believed deeply in the psychological effects of color. Yellow, for example, had an expansive, energetic quality, while blue suggested depth and introspection. The interaction between these hues creates a sense of visual tension and excitement.

- Lines & Motion: The use of diagonal lines and intersecting curves creates a rhythmic quality, reinforcing the idea of ascent. Rather than a static composition, this is an image in motion, a structure that appears to be growing, shifting, and transforming before our eyes.

- Geometry & Spirituality: Kandinsky’s forms are not merely aesthetic choices; they carry meaning. The triangle, often associated with spiritual ascent in his writings, plays a dominant role in this work, pointing upward like an arrowhead. The circle—another key Kandinsky motif—appears as a stabilizing force, symbolizing unity and wholeness.

Kandinsky’s Synesthetic Vision

Kandinsky famously experienced synesthesia—a condition where one sense involuntarily triggers another. For him, colors and shapes corresponded to specific sounds and emotional states. He described yellow as “lively, eccentric, and slightly aggressive,” while blue was “deep, peaceful, and spiritual.” He often spoke of seeing musical compositions as colors and forms in his mind’s eye. Joyous Ascent seems to encapsulate this idea perfectly: a rising melody of hues and shapes, an abstract crescendo that lifts the spirit just as it lifts the gaze.

This connection between music and painting wasn’t just a personal quirk; it was foundational to his artistic philosophy. His 1911 treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art argued that painting should strive for the same non-representational purity as music. Joyous Ascent embodies this belief, functioning almost like a visual score—one that doesn’t need lyrics or notes to convey its meaning.

From Russian Avant-Garde to Bauhaus Geometry

Kandinsky’s journey from his early expressionistic works to his Bauhaus-era compositions is a fascinating evolution. If we compare Joyous Ascent to his earlier paintings like Composition VII (1913), we see a shift from fluid, chaotic brushwork to a more structured, geometric approach. This transformation was not a departure from his spiritual goals, but rather a refinement. He was distilling his vision into purer forms, stripping away excess to reveal the fundamental principles of visual harmony.

This transition was influenced by his time in Germany, where the intellectual rigor of the Bauhaus reshaped his methods. Yet, even within this framework of precision, Kandinsky never lost the essence of what made his work so profound: the belief that art had the power to move, uplift, and transcend the material world.

A century after its creation, Joyous Ascent remains as compelling as ever. In an era where digital design and algorithmic precision dominate visual culture, Kandinsky’s hand-drawn symphony of forms feels refreshingly human. His ability to infuse geometry with feeling, to make color sing and lines dance, ensures that his work continues to resonate beyond the confines of art history.

For those who encounter Joyous Ascent today, the experience is much like the one Kandinsky intended: an invitation to see beyond the surface, to feel the hidden rhythms beneath the forms, and to let the eye and mind be carried upward in an ascent that is indeed joyful.

This article is published on ArtAddict Galleria, where we explore the intersections of art, history, and culture. Stay tuned for more insights and discoveries!